Prostate Cancer: We begin the dive into higher risk disease

To date, we've looked at low and intermediate risk disease, today we start to examine a big bucket with far more variety - high risk prostate cancer.

www.protons101.com

Home to the musings of a radiation oncologist - with a slant on protons and dose and optimizing cancer outcomes.

High (and Very High) Risk Prostate cancer:

It is a broad topic - so much more diverse than intermediate and low risk disease. A grab bag of disease covering locally aggressive disease to even lymph node positive cancer.

It’s been on the to do list, but it’s been a while in the making. I honestly have a little less clear definition on the path forward so it will be interesting to me to see where this dive into our data and trials on the horizon will lead. And like I often will do, we need to come to a basic understanding of context - by that, I mean, I need to verbalize how I mentally file these more aggressive cases and then explain to you that I believe we must adjust a bunch of key fundamentals that I rely upon in lower risk disease.

In this Substack on prostate cancer, I’ve focused on three primary issues for prostate cancer:

1) Dose: (an example of several articles on the importance of dose)

2) Avoiding ADT if possible (a discussion of using more dose to minimize ADT usage)

3) Using PSA kinetics: (an early metric to help us make faster and better judgements to assess outcomes and minimize risk of less ADT usage)

The Three Pillars - Redefined:

So before we begin to discuss options and directions, I need to explain why each of these three pillars that I lean on for low and intermediate risk essentially fall apart once we get to high risk disease.

It really is quite simple - in lower risk disease - disease that we can cure say 92% of time at 5 years with radiation alone, there is limited metastatic risk at presentation and a great opportunity to avoid ADT.

As we’ve reviewed, I think I’m a bit of an outlier and not afraid in places to push beyond NCCN which I think emphasizes ADT too much. For example, today in my running database, 65% of unfavorable intermediate men I see end up opting to avoid ADT after we discuss the data. As we’ve reviewed, this cohort has a PSA <1 at 1 years and is <0.5 at 2 years - mean - not median. So like I’ve argued at length - hit good metrics that should lead to very strong long-term outcomes and you have a good program. If you can do that in 2 fractions and manage toxicity - that is great. If you need 35 treatments and approach it like FLAME did - again, that is great. If your practice isn’t meeting those kinetic goals, then I would personally use more ADT. What we want to achieve is great consistent results for our patients using the least toxic approach for our patient population.

I’m sure there is a subset of intermediate risk cancer patients who still really require ADT (or pelvis treatment, or both maybe), but from my data and my experience, in the subset of men I treat, I think it is less than 35% of unfavorable disease IF you push dose - whether protons affect that at all - I’m less clear.

But in high risk, currently I’m quite hesitant to avoid ADT altogether. And that impacts my 3 pillars of dose, avoid ADT, and kinetics.

But first, an aside - kind of.

In Science, Details Matter:

The initial goal of this post was to explain basic differences between our ability to assess and compare high risk outcomes to intermediate and low risk disease. The implication is that ADT has tremendous impact that directly affects all three of my central points on intermediate and lower risk disease.

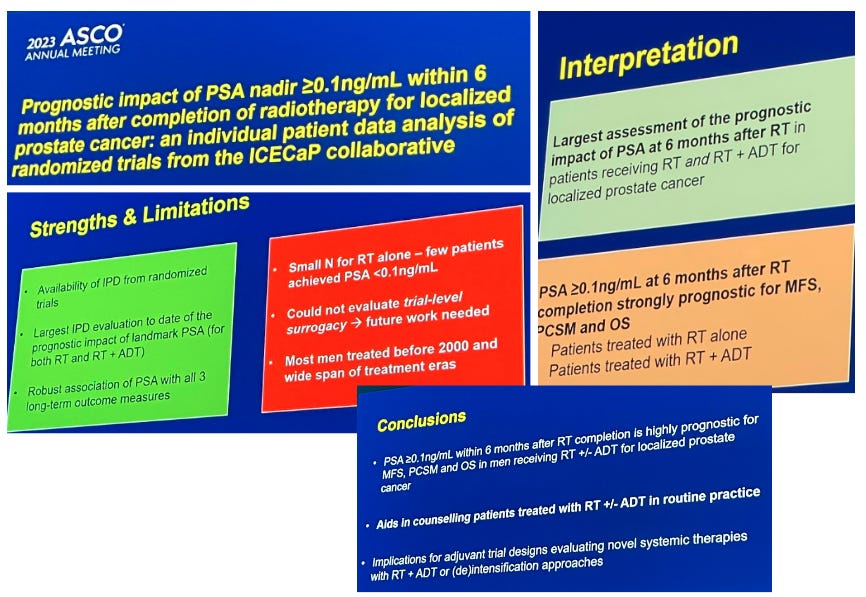

And yet, just this past month at ASCO, one large talk had slides that completely ignored this reality. It is, to me, a massive error in logic. Here are the slides:

Five times in 4 slides, PSA kinetics are grouped together for radiation alone AND radiation + ADT. Yes, the small numbers are listed as a limitation in the radiation alone arm and there is a slide (not shown) that documents only about 2% in the radiation arms achieve a response of 0.1 or less but this isn’t one or even two mentions. Instead the authors clearly opt to bundle radiation alone patients into nearly all conclusions. I posted my concerns and I did get this response back with regards to my question from an author of the trial:

The main implication of these data is for patients receiving RT+ long-term ADT for high-risk disease and potential (de)intensification in such patients.

That statement I agree with. I don’t believe the slides represent that tone.

Here’s why this is important: This is not nuance - lumping radiation without ADT into a kinetics discussion and then discussing 0.1 as a 6 month evaluation point, to me, demonstrates a lack of understanding of PSA kinetics following radiation - a complete lack of understanding. Do I doubt that the database has those numbers in 2% of cases? No. Do I doubt the statistics? No. But I also appreciate just how nuanced understanding post-treatment PSA kinetics is on a broad scale - it is like proton therapy, only a subset of radiation oncologists really appreciate the details and nuance. So to see these headlines is simply frustrating and to have it inappropriately amplified at a big meeting is quite disappointing.

In science and research, both details and broader context matter - as scientists and those that read the medical literature, it is incumbent upon us to be skilled at the merger of these two widely divergent perspectives. We must view both the forest and the trees at the same time and when we present, we should be able to convey that blended perspective - that is what the best do.

A Comparative Look - my database:

I reviewed my database and out of 150+ patients treated with radiation alone - 2 hit 0.1 or less within 6 months. And as we discussed I believe this cohort of patients is on pace to achieve at least 85% and likely closer to 90%-92% DFS based on kinetics - the cohort is below a mean of 1 at 1 year and <0.5 at 2 years.

As for the two patients? I reviewed charts - one was GG5 disease on a ton of supplements for a few years trying to control disease and actually got a drop of over 1/2 in his PSA using these approaches. He refused traditional ADT and PSA went very low, very fast. I really believe somehow, his supplements altered the response or baseline hormone levels but I didn’t check labs as he wasn’t “on ADT” - based on PSA response, I know wouldn’t say that. The second patient had a PSA drawn 6 wks following the 1st treatment (basically last day of a hypofractionated radiation course of treatment) and it was 0.4 from around 8 pre-treatment. It was 0.1 at 3 months. I know the surgeon and although I can’t find it medical documentation - based on the surgeon and practice patterns, a hormone shot was likely given - no guarantee but a documentation oversight error is more likely in my estimation - next visit - I’ll ask the patient.

In my estimate, this meta-analysis is seeing the same thing. I presume the majority of the 2% cohort actually is due to some form of testosterone change that is driving this super fast decline. Maybe 0.5% hit that mark truly with no odd history but the majority of their “findings” I believe represent error. I asked some people with larger databases to look - haven’t heard back to date.

But their simplistic conclusion? Sure. Do I believe lower earlier better? Yes. Is 0.1 at 6 months even something to consider with radiation alone as an expectation? No. Look beyond the trees that appear in the column of the database and get produced by the statistical program.

I honestly nearly skipped writing this context portion of this article - I thought it was so obvious but I had it in here and then this dropped online via ASCO and, in hindsight, I should have written this article earlier.

So the requirement of ADT changes the context - not just for one pillar but all three.

ADT: Instead of Avoid, I Minimize:

Several years ago, I saw a paper that talked about patients on ADT and receiving radiation should hit a nadir of 0.2 or less with 6 months of completing treatment. It made sense and since that time, I’ve watched about 100 men and it seems like a rather reasonable market - that if men do not hit that level, they are an outlier. And in fact (back to my database), in my patients 8% or so are >0.2 at the 6 month mark post treatment with ADT and radiation. If you look at >0.1, that number moves to 15%.

So for the last few years, I have a post-treatment marker that I use to help in determining whether patients have a stronger opportunity to discuss and decide to stop ADT following treatment. I use three items to make these calls:

My Baseline Clinical Estimate: My general high risk recommendation is 18 months. Very high or LN+ and baseline is 24 months. Low Decipher in clinically high risk patient and I might push this initial recommendation toward 12 or 6 months but today, my patients really have to insist on no ADT and we have frank discussions about clear increases in metastatic disease and likely prostate cancer mortality if ADT is avoided in high risk prostate cancer patients.

Tolerance of ADT: some men it doesn’t bother, others really really don’t like them. Tolerance enters the discussion as we move beyond treatment. This goes into the discussion as well as co-morbidities, specifically weight gain, diabetes, and cardiac disease risk factors.

PSA response at the 6 month mark: Lower is better. Not yet at 0.2 and we probably really need to stay the course.

That is a brief summary of my approach. If I seemed to have missed or forgotten something, please comment.

But I think that begins to show the trouble with absolute answers in high risk disease - there is tremendous variety. Variety in the risks of the cohorts you see, variety in ADT, and variety in approaches which I believe will make it difficult to use a high risk cohort to demonstrate precisely which doses are better than others. While I dislike ADT due to its toxicity, it is a wonderfully effective treatment for prostate cancer. Works nearly every time and gives men even high risk / or very high risk disease great opportunities to have strong outcomes years after treatment with radiation and ADT. If we need them, they are a terrific option.

But within my practice, I’m on the lighter / shorter end of standard of care. We have a number of discussions around the 12 month mark to access patient thoughts and goals and discuss the risk / benefits of continuation vs. stopping a bit early. And with that context, we can move to kinetics: the second pillar to fall.

PSA Kinetics:

We’ll just keep things simple - you have two primary options. You can choose the longer standing data point of 0.2 or less at the cutpoint for what we need to hit after 6 months or you can use 0.1 or less per this new analysis (ref 1,2,3). Higher than these don’t make sense as will be evident when we look at data.

Is 6 months exact even one moment in time? No - and in fact, it is good to understand that it has shifted over the years. For example, since the treatment for the data in the current slides we reviewed above a few important things have changed.

ADT has moved from neoadjuvant setting to concurrent / adjuvant approach based on data suggesting superiority of adjuvant ADT. (ref 4,5).

Today we have hyofractionation - so from the start of treatment to the “6 month” post-treatment mark - we have about 2-3 fewer weeks - up to 6-7 if you are in an SBRT program.

Each of these are significant changes with respect to a short term data point. So my simple answer is that I’ve leaned on 0.2 as my cut point to help in my decision making.

But when we get new data - even data that we where we don’t like the slides - it is good to evaluate and consider the premise and the conclusions.

Once again, a look to my database:

Of ~100 patients in receiving treatment with ADT and hypofractionated courses of treatment 8% have not achieved 0.2 or less and about 15% did not achieve 0.1 or less at 6 months following treatment.

So based on this and paired with the new data that was reviewed - even though I really really dislike the slides - I’ll probably move closer towards 0.1 or less to shorten ADT duration and be a bit more cautious in that 7%-8% that lie between 0.1 and 0.2. If you consider my general approach, I’m already on the shorter end of standard of care recommendations and I am using this to de-escalate ADT duration further in some. Within that context, remaining more firm in my recommendations for 15% of patient (allowing 85% more flexibility to de-escalate ADT duration after discussion of risk / benefits) seems like perhaps a more reasonable balance point.

Again, I like reconciling outside data with my own outcomes.

Dose: The final pillar

Will it even matter in high risk disease? Yes.

But it will covered up with far more noise in the data. Variety is noise and simply the high risk and very high risk stages contain vastly more risk variety. Low risk is amazing consistent in prostate cancer. Even most intermediate risk is pretty well defined, but in high risk, you leap into a wild basket of unknowns.

Let’s just take an example - yep, back to my database - it is easy to evaluate and compare alongside a study out of India. This comparison demonstrates quite clearly that even within high risk - there is a massive level of risk difference possible between two datasets.

In the PRIME trial, which we will review in more detail an the upcoming post, 75% of the enrolled population is high risk or very high risk - but 20% are lymph node positive. Compare that to my series: PSMA went live in Oklahoma City in around February of 2022 (so about 1 month post Medicare approval) We were not an early market in the US. In my series, 1 patient of 250 is lymph node positive. Of the high risk / very high risk cohort, 1 of ~73 is lymph node positive. There is a chance I haven’t included a couple on my initial grab of the cohort but it is very uncommon for me to see lymph node involvement at presentation. Certainly <5% of my HR / VHR cohort.

The point is: high risk in OKC is not high risk in India. But low risk is pretty much low risk.

So we have massive variety in the initial disease and as I’ve reviewed, at least in some practices: there is nuance in ADT which is a primary driver of outcomes for at least 5 years - it dominates the clinical picture for 2 years in high risk and only in year 2-3 (or 4-5) can one begin to see differences in radiation - ADT is simply that effective.

And so while dose is important a 5% dose difference will be easier to discern differences in effect in intermediate risk without ADT than in a high risk cohort with ADT. So with that in mind, I believe you need to hit reasonable marks for good dose and at that point, volume - pelvis vs. no pelvis is probably more important to the outcomes.

Pelvis or No Pelvis:

A quick note on pelvis / no pelvis

I’m biased - trained at MDACC and we didn’t treat pelvis. I’ve been slow to adopt and while I use it in some cases, I probably use it in less than most - again - context is good.

A second manner in which I’m biased. If the trials go back 20 yrs or so, I’m less clear they still apply today. Some in our field really like really old data. I think it was a bit different disease and treatments were quite different. Some principles apply and others, I’m less convinced.

So with that, I’ll point out two takes on our literature. One is an editorial by leaders in the field arguing largely against widespread adoption of whole pelvis and the second is a rather modern prostate trial showing benefit.

An editorial against broad treatment of the pelvis:

Elective Nodal Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: For None, Some, or all?

It is well written and focuses on older studies (ref 6), primarily RTOG 9413 (treatment from 1995-1999) and GETUG-01 (1998-2004). One old and one really old. Neither showed benefit - 3D CRT - dosed to 70Gy - like I said, old studies. But the point that both were negative is fair - these are prospective randomized trials. And they lead up to RTOG 0924 which the editorial claims will be the “definitive trial” - except it doesn’t include PSMA imaging and so once again, I’m less convinced. But it presents very reasonable arguments against routine use - many of which I agree with. I would encourage you to read it.

More recent data argues in favor of treatment:

On the other hand, two more modern trials seem to demonstrate support for pelvic treatment. The POP-RT trial (ref 7) out of India and back to a mentor of mine - Alan Pollack with the SPPORT trial (ref 8) - notably in a different setting of post-surgery salvage treatment.

The stronger of the two in the discussion of high risk disease is the POP-RT trial. Straightforward design out of Tata Memorial in India. The trial delivered radiation with 2 years of ADT for high risk men node negative men (Roach formula >20% risk) and randomized the radiation to prostate / SV alone or inclusion of the pelvis. Amazingly, it included PSMA PET imaging in 80% of patients despite starting in 2011.

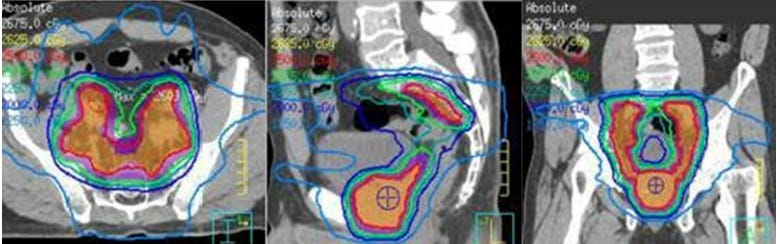

Doses are reasonable, and modern by today’s standards, with 50 Gy to the pelvis in 25 fraction and an SIB boost to 68 Gy in 25 fractions to the prostate. For the prostate, that delivers an EQD2 (a/b=2) of 80 Gy via a hypofractionated approach. Not super high, but strong baseline dose.

And it shows a quite dramatic improvement - with disease free survival increasing from 77% to 89.5% with the addition of pelvic treatment.

The SPPORT trial does something similar in the post-surgical setting and again shows significant gains with the addition of larger fields - I think most view it as supportive with the primary dataset being the POP-RT trial.

So in India, we see clear benefit of about 12%-13% improvement in disease free survival with the addition of pelvic treatment in a trial that is far more current - additionally it incorporates PSMA imaging and utilizes reasonable hypofractionationed treatment.

My quick assessment: Data wise - I think improvement in disease free survival is better represented in the POP-RT trial and supports use in that cohort. But toxicity wise, I personally see more bowel toxicity with pelvic treatment. It shows up in the data and I see the difference in clinic. It is manageable but I think it is real. And then, in my clinic, where I don’t have pencil beam, uniform scanning doesn’t do great work in treating the whole pelvis so if you roll all of those into one statement you get,

My Clinical Approach: Less pelvic treatment than most

But, I don’t think one can argue if you opt to simply mirror the POP-RT trial exactly. It is easy and straightforward and the Roach formula has been around since 1994. An amazing accomplishment to have it still in use today.

What might change the outcome in your patient population:

Generally if we push doses higher, the absolute difference should lessen.

A different baseline risk of lymph node involvement.

Of the two, dose is likely the less impactful. But baseline risk for the US vs. India I don’t think should be discounted. If, for example, cases sit untreated for a year or two or five longer in India than in the US, then perhaps with PSMA, you can scan and filter out the fastest growing tumors, leaving those that are lower risk but still, with time and far less awareness of prostate cancer in general, have real nodal risk. Compared to the US where they might have the bump in PSA and within 6 weeks be considering treatment options - they are different scenarios and perhaps have an impact.

Fortunately for me, while the topic of high risk is broad, I think we have some great trials to look at to help guide us into the future. In the weeks ahead, we’ll look at some of the ongoing studies and talk about the manner in which I think they effectively address a lot of questions that we need to see answered.

As always, thanks for reading and consider subscribing or sharing. It really does help to promote the work here. To those that are new to the Substack - thank you for your support.

REFERENCES

Achieving PSA < 0.2 ng/ml before Radiation Therapy Is a Strong Predictor of Treatment Success in Patients with High-Risk Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6854218/Absolute Prostate Specific Antigen after 6 Months of Androgen Deprivation Therapy Is a Predictor of Overall and Cancer-Specific Mortality in Men with Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

https://www.auajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1097/JU.0000000000002676Duration of androgen deprivation therapy with maximum androgen blockade for localized prostate cancer

https://bmcurol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2490-11-7Neoadjuvant versus concurrent androgen deprivation therapy plus radiotherapy for unfavorable intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer with low PSA.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2021.39.6_suppl.243Prostate Radiotherapy With Adjuvant Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) Improves Metastasis-Free Survival Compared to Neoadjuvant ADT: An Individual Patient Meta-Analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33275486/Elective Nodal Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: For None, Some, or all?

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360301621026018?dgcid=coauthorProstate-Only Versus Whole-Pelvic Radiation Therapy in High-Risk and Very High-Risk Prostate Cancer (POP-RT): Outcomes From Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33497252/The addition of androgen deprivation therapy and pelvic lymph node treatment to prostate bed salvage radiotherapy (NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT): an international, multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01790-6/fulltext