RAPIDO Rectal Cancer Trial: Another Example Where EQD2 Dose Matters

In the most recent release from the RAPIDO trial we see that dose likely matters. Less dose and the effectiveness of the radiation decreases.

www.protons101.com

Home to the musings of a radiation oncologist - with a slant on protons and dose and optimizing cancer outcomes.

I tend to file things broadly - match up data sets and mentally mark them as consistent or inconsistent. Look at my article here comparing the MIRAGE trial to the Esophageal Prospective Proton data as an example of a rather unique comparison across widely divergent datasets.

For me, the most valuable concepts appear across multiple sites and can be demonstrated in a variety of settings. It is part of the benefit of being a radiation oncologist who treats a little bit of everything - a broader perspective and not just deep in a single cancer subsite - it matches up well with how I tend to organize my thoughts so I go with it.

And today, we’ll look at another recent trial released this year that again demonstrates my belief that we’ve focused at least a bit too much on shorter and not enough on better outcomes. As I discussed a few months back, the pendulum just needs to drift towards neutral a bit more - one isn’t wrong and one isn’t right, it is a search for balance.

The RAPIDO Trial:

There is a tremendous Twitter thread by Dr. Emma B. Holiday that gives more background history for those who are interested - I’ll focus more on the here and now, she gave a broader historical perspective. She is a focused worldwide expert in GI cancer, I’m a generalist. Trust her voice. If I write something interesting, perhaps consider mine. :)

As always, if you see me missing something, speak up. Most articles I tend to write have some slant that I think is unique or might counter the common narrative - hence some opportunity for questioning and maybe altering perspectives - so quite possible I’ll be off in places and proven incorrect. Feel free to comment or reach out to me. I’m happy to fix or address anything or host counter views.

Dr. Holliday Twitter Thread: Worth a read…

https://twitter.com/DrEmmaHolliday/status/1649787965340622848

In summary, she walks through history and then focuses on the RAPIDO trial which was released Jan 2023 - it is five year follow-up of the trial that was one of the major trials used to justify short course (SC) 5 fraction pre-operative treatment. As she explains, it was announced that it met its primary endpoint of improving disease free survival at ASCO 2020. It was released at the height of covid - and we loved it - less fractions, less time in clinic, less exposure. A win, win, win!!!

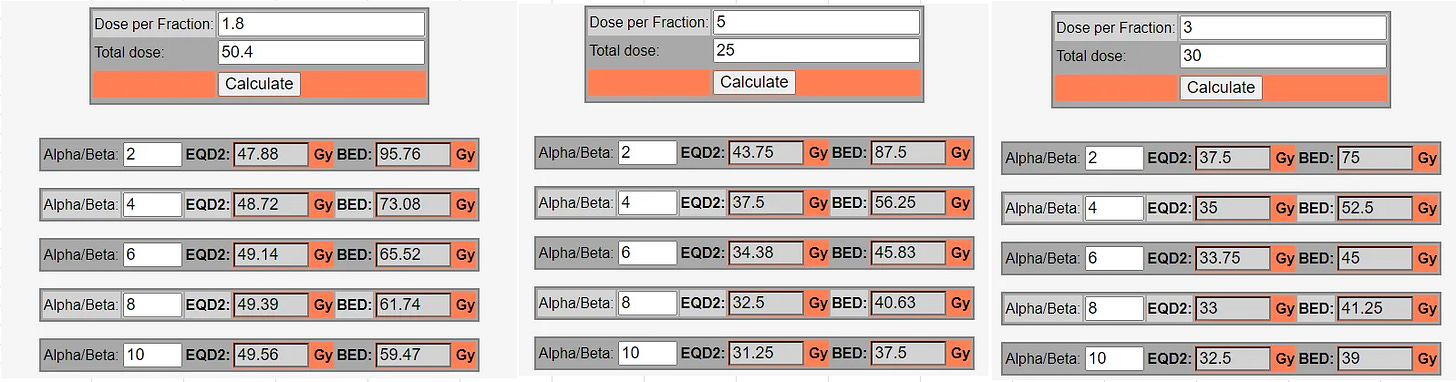

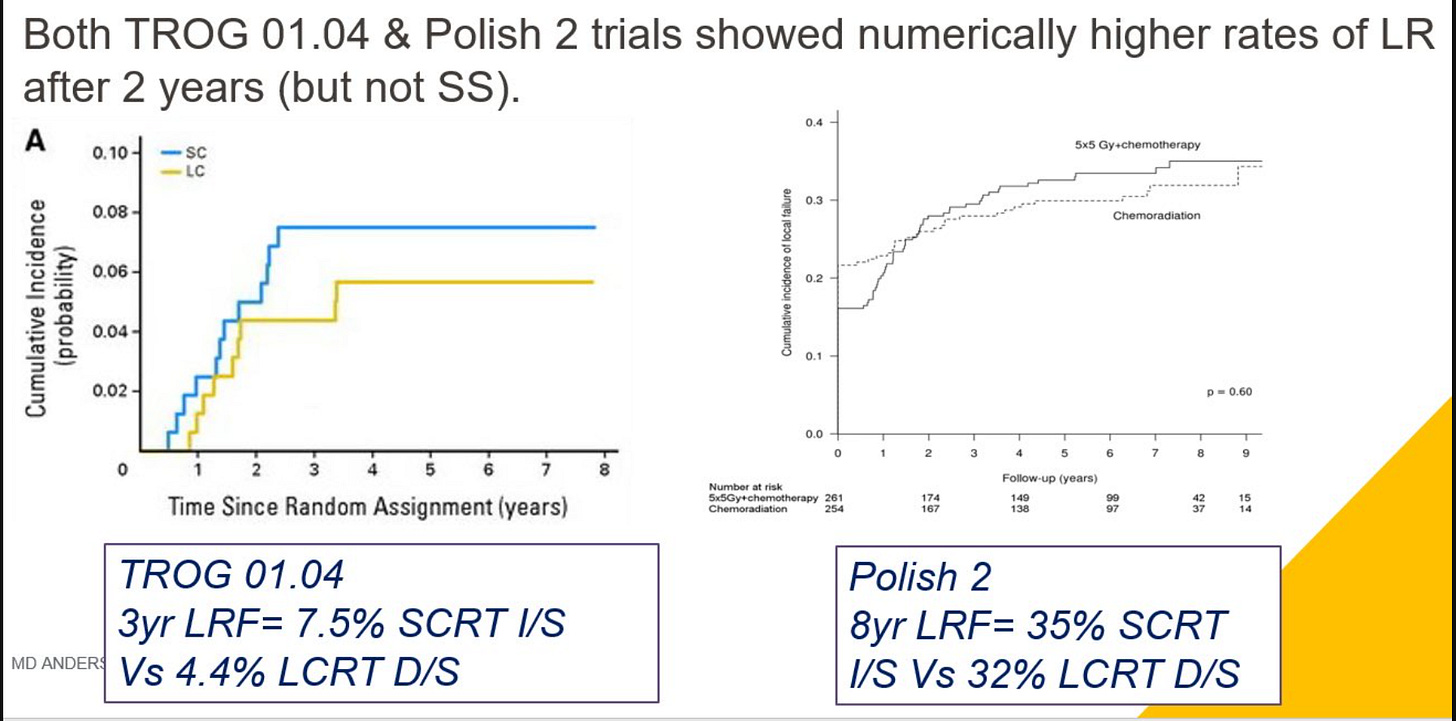

But later, as the first manuscript dropped and then again in an ESSO presentation in late 2021, there appeared to be a increase in local failures. And yes, that makes sense because 25/5 is less dose - it is likely <40 EQD2. (we’ll come back to that number in a moment).

And now in 2023 the five year results are out (ref 1) which show: a significant increase in local failures with 5 fraction short course along with more breaches of the mesorectum - both are poor outcomes and both were statistically significant.

Here is one of her tweets:

Yep. Completely agree - we need a high bar to lower dose. Shortening time is different from less dose. We need to separate the two mentally - they aren’t just different files, they need to be in completely different file cabinets in your mental repository. As I’ve discussed before, I believe we sometimes merge the two under a more generalized “SBRT” filing approach - I believe this is an error.

It is important to point out that the RAPIDO trial is NOT just a radiation dose trial - so the dose comparison is not the only variable. This does open up other additional arguments that are beyond today’s scope. Briefly here is the trial structure that illustrates there is a potential for something more complex than dose alone.

Two arms of RAPIDO Trial:

Standard: 45-50 Gy with capecitabine > surgery > selective post-op chemo.

Experimental: 25 /5 Gy followed by full dose chemotherapy with capecitabine / oxaliplatin > surgery.

But as she notes, the trend isn’t just here in the RAPIDO trial - it was in some older data as well looking at short vs long courses (less dose vs more dose):

And one last point which is critical to the context of our discussion - the historical use of radiation in rectal cancer is specifically to improve local regional control. It doesn’t affect metastatic disease occurrence or overall survival. It is a local treatment designed to stop a really bad outcome of a deep recurrence within the pelvis that can lead to terrible pain. Historically, our mission was local control, and this appears to compromise that basic mission.

(Today we are using radiation, in some cases, as a substitute for surgery which we’ll touch upon below.)

So what is the equivalent dose?

I’m not sure we know. The clinical data above suggest it is less. The radiobiology literature is frankly a mess. Here is the most quoted reference paper I found:

The alfa and beta of tumours: a review of parameters of the linear-quadratic model, derived from clinical radiotherapy studies (ref 2). 314 citations - published in 2018.

So 2.7 to 11.1 with studies with a “non-confidence” interval of -11 to 33. Ok, lets just look at a range from 2-10. It is likely in that range for an alpha beta for rectal cancer. (a stats joke followed by a radiobiology joke - wow)

Long course has traditionally been ~5040 / 28 (the RAPIDO was technically two options 45 / 25 or 50 / 25 so this will split the difference). Regardless of your thoughts on the alpha beta, 25 / 5 is less dose. A lower alpha / beta reduces the difference, but short course appears to be less dose. In fact, it is likely closer to 3000 / 10 than it is to our standard pre-operative historical standard.

I hate to admit that until this year or so, I didn’t realize that. I have never really looked at moving to a 25 / 5 approach. I read the headlines and I assumed the doses were pretty comparable. They are far more different than I appreciated.

So how did we get here?

In other countries, healthcare markets are different - resources are limited and there very well might be appropriate needs to reduce fractionation to increase throughput, but in the US - I don’t believe this is the primary driver for this shift.

Shorter treatment courses have been around for decades so there is very valid historical context. The Uppsala trial (ref 3) is a trial out of Sweden from 1980 to 1985 - one arm was 25.5 Gy in one week in the pre-operative setting. So we literally have been here for four decades.

Further a short course approach does have concepts for faster times to systemic chemotherapy or quicker to surgery but today I don’t see those as the central rationale for this approach more broadly, but I do think these contributed to the excitement around this approach and perhaps some of the early work in this direction.

Dr. Holliday then relayed about a story by one of her mentors - it went like this:

short course radiation was born when a surgeon said- “sure you can do preop radiation if you want- but I’m taking the patient to the OR next week- so do what you can in 5 days”

It might not be that far off.

For large centers, it does have benefits. Shorter definitely helps with patients travelling to big centers for care. But consider this: would anyone travel to a big center IF they knew the treatment at the big center was shorter and more convenient to offset the drive / travel time? And in fact data suggested it was likely less effective than the treatment closer to home? (I guess arguing that they’d make up the difference in cancer team approach or maybe it would benefit patients five years into the future?) Regardless, I feel quite confident in saying it would be a less successful marketing approach.

So control is not better. Data appears to be showing it is likely less effective at current recommended doses. And this is supported by the fact that our current recommendations are almost certainly less dose, unless our basic understanding of EQD2 for SBRT is wrong (I don’t think this is impossible, but unlikely).

What about toxicity? Less dose - maybe toxicity is markedly less.

But I don’t think that is the rationale for this shift either. Here is a recent discussion with a second GI expert radiation oncologist - Dr. Nina Sanford. It is from The Accelerators Podcast “We Tried Adding the Mustard”: Rectal Cancer With Nina Sanford where she discusses toxicity. It is a very good listen - recommended. As she described:

And I do think for short course, when I counsel patients between short and long course I them that toxicity wise - toxicities from long-course radiation are a lot more predictable and you’re seeing the patient during treatment so you can help them through the treatment. Short course as you all know - the side effects don’t come until 1.5 - 2 weeks after and its a lot less predictable. So some patients sail through and have like nothing, and some patients are completely miserable after and are like hospitalized and really suffering…

Please remember, I’m not saying toxicity is more with short course - I just stating that I don’t think you can make an argument that we moved to short course to reduce toxicity - it is less dose but in a shorter time period and in the pelvis where volumes aren’t small, these changes - generally speaking - don’t lead to a large reduction in toxicity with shorter courses despite less dose.

Which leaves me to think the answer is, at least in part, convenience and, on some level, marketing and a “cool factor” that it can be done so quickly - at least in the US.

I’m an engineer. I like data. I dislike marketing and “cool factor” and the word “excitement” in medicine. Feel free to laugh - it is appropriate. I write this from a proton center - which is more than a little ironic. But I came here for first hand knowledge and experience - to try to remove the issues of marketing campaigns and promises and to see for myself what I thought of the technology. Again, the goal is to use data and my experiences over headlines and I wanted to be on the front line of the debate regarding proton therapy.

This year, I refocused and began this dive into our literature. In just a few months, I think this represents a second instance where at times our field of radiation oncology is pushing quite hard towards preferring less fractions and convenience / costs while, on some level, probably compromising on clinical cancer outcomes.

It has been something I stumbled upon - just reading the headlines and starting to dig into our data. My initial goal was to review a few proton related articles. I wanted to argue about the need to really focus on outcomes, but the last two months have largely ended on this issue of delivered dose - mainly from a prostate cancer perspective.

Frankly I didn’t expect to find this and, to me, it is disappointing on some level. I don’t think I should be able to be in private practice in a community setting for over two decades and find rather large (to me) flaws or issues in our literature relative to a “consensus” path forward. Maybe it is that rather unique history that lets me consider different viewpoints - I’m not sure. Maybe that is why our field is struggling a bit relative to other specialties - again, I’m not sure.

And while it can be frustrating, I think it is exciting - I think we, as a field, have great opportunity for improvement and young physicians therefore have remarkable opportunities to influence our path forward asking pretty simple questions like: “Can we do better?”

So here in rectal cancer, it is appears to be a small decline in local region control. Not definitive, but enough to hopefully give people pause while we sort out possible options other than the most apparent answer: dose matters. And in prostate cancer, we have similar data where we aren’t pushing for dose escalation consistently even though randomized prospective data demonstrates improvement in cure rates.

In prostate for example I believe we have four relatively “established” methods to safely escalate dose, yet these are generally under utilized today and none would be considered “preferred” according to our NCCN guidelines:

MIRAGE Trial - 40 Gy with some SIB to 42 Gy within a 5 fraction approach - if your program can deliver that dose and keep toxicities manageable.

Escalation of hypofractionated approaches - UFPTI approach to 7250 / 29 fractions or look to PACE B using 6300 / 20 fractions.

I prefer these over lower EQD2 dose SBRT treatments or hypofractionated approaches for most intermediate risk men - especially for those in whom you are considering ADT.

SBRT:

Remember my stance - SBRT is the single greatest example of progress in our field in the last 10 - 15 years - prior to that it was IMRT. SBRT is / was great because it dramatically improved cure rates for some cancers using higher doses to smaller targets. It was not our greatest accomplishment due to being shorter. Shorter is a side benefit but the primary benefit is better cancer outcomes.

Will Short Course Rectal Treatment Go Away:

To her credit Dr. Holliday asks this directly and then responds with candor I seldom see in social media suggesting a shift away from short course for many patients with rectal cancer.

Kudos! I love the thread and the acknowledgement that shorter isn’t always better - the pendulum swinging back in real time.

We all know that it won’t go away and it shouldn’t.

Breast Cancer APBI: A look at perceptions and expectations.

As another example in a nearby mentally filed folder, just look at the breast accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) experience for where this might go. (I know this is another, perhaps, sensitive topic, but to me, I do file it nearby).

Today we quote one main trial for APBI - the Florence Italian trial (ref 4) - published Sept of 2020.

10 yr follow up - 520 patients - less acute toxicity, less late toxicity, better cosmetic outcomes - excellent control. It was 5 fractions, consistent with our seemingly near “consensus” vision of where we want to go - smaller, quicker, convenient treatments. And it quickly became standard.

But just 10 months before that trial was the Whelan (RAPID) data (ref 5) - bit different approach (twice a day treatment to 38.5 Gy), different technically (3DCRT) but 2135 women - a far larger trial - four times the number of women.

And long-term - we missed. ~20% more women had Grade 2 or higher toxicity and adverse cosmesis was 17% worse in the short course partial breast arm. Here - like in the RAPIDO trial, we thought we had it figured out but with longer time periods, chinks in the armor appeared.

Fortunately for our narrative (my term), the Florence trial quickly “fixed the issue” - long-term excellent results - 5 fractions worked! We *think* it is a combination of IMRT and losing the twice a day treatment approach but maybe it is in the nuance of the approach as well.

But Florence got us back on consensus path - shorter is better and quite doable.

My use of APBI as an example is both good and bad - it is an example of how we tend to believe some data more than others. It is a poor example in that 30 / 5 is about the same dose as the comparative whole breast schedules, but I thought interesting enough to include - perceptions and the consensus view frame so very much of our interpretation. (I think it applies to some extent in our acceptance of 26 / 5 for whole breast approaches which is a bit less dose)

From my perspective, across some 50 trials, short course / SBRT is closer to the razors edge. A finer line between good outcomes and high toxicity outcomes. Makes sense but that leads to more nuance - nuance often beyond the contents of the publication.

Me: I agree once a day and IMRT probably do represent the difference to safely allow 5 fraction APBI, but I’d follow every one of my patients for 5+ years and self assess the nuance of my plans. And I’d include some additional risk statements in my consent process related to the Whelan data.

Back to rectal cancer:

In a similar fashion, I feel quite confident we’ll adjust and largely continue along our current path with rectal cancer. I do think this data will greatly amplify the number of people treated with boosts to 30 / 5 which gets us into the realm of dose that I think will be equivalent but almost certainly with some additional toxicity risk. Like in the breast cancer example above, there is simply a ton of momentum in this direction.

But off study and in the community, I think many physicians and patients can feel comfortable today that treatment to 5040 cGy in 28 fractions was / is really good treatment - likely producing better cancer outcomes for most patients than short course - despite a 10:1 ratio of comments on social media, in marketing campaigns, and in the headlines celebrating the shorter approaches.

I’m old at this point I think - 20 yrs in and probably quite stubborn. For me, over the next 5 years after this setback, I’d rather see us push this dose a bit higher to 5400 or up towards 6000 in some cases to try and minimize surgical resection for people via traditional fractionation or hypofractionation - the podcast covers very interesting options of traditional fractionation up to 6200 cGy in the literature or even pulse type approaches with monthly large treatments.

Let’s finish there: Dose escalation via 28 fractions

Curative chemoradiation for low rectal cancer: Primary clinical outcomes from a multicenter phase II trial.

This is a phase II dose escalation trial out of Denmark. It has been presented at ASCO last year in abstract form where they presented the primary outcome (ref 6). Learned about it on the podcast with Dr. Sanford - again always listen carefully to experts.

It is a dose escalation study attempting to avoid surgery for patients with low-lying rectal cancers. They delivered 50.4 to the pelvis and performed an SIB boost to the primary tumor volume to 62 Gy along with Capecitabine 825 mg/m2 BID. This is an EQD2 dose of 63 to 64 Gy (a/b range of 10 to 4. Note the minimal effect of a/b with more fractions). These were low lying rectal cancers where APR or ultralow resection was required (specifically <6cm from anal verge)

Enrollment was at 3 Danish centers - 107 patients. Baseline classifications were T1/T2/T3 and N1 in 15%/54%/31% and 29%, respectively.

Below are the outcome measures:

Primary Outcome Measures :

Proportion of patients with locoregional tumor control with chemoradiation alone two years after end of treatment [ Time Frame: 2 years after end of treatment ]

Secondary Outcome Measures :

Cumulative incidence of local recurrence after surgery [ Time Frame: Every two months the first year, every three months the second year, every six months the third year, and annually the fourth and fifth years ]

Rate of distant metastases [ Time Frame: Every two months the first year, every three months the second year, every six months the third year, and annually the fourth and fifth years ]

Response and tumor control on MRI scans compared to clinical observations, including rectoscopic examination [ Time Frame: 6 and potentially 12 weeks after end of treatment ]

And the results:

61% (63/103) with 2 yrs of follow-up had tumor control with chemotherapy and radiation alone. The most severe toxicity was erectile dysfunction. 23 of the 103 did have regrowth after chemoradiation. 5 of those had transanal endoscopic microsurgery, 15 other had curative surgery, leaving 3 of 103 with palliation following treatment.

Metastatic free survivial was 85.4% and overall survival was 94.8% at 30 months (need more time for this data to mature).

Conclusions: The vast majority of patients with low rectal cancer can be cured by modern radiotherapy 62 Gy in 28 fractions with excellent patient-reported outcomes, toxicity, tumor control, and survival. The treatment is feasible in a multicenter setting. We suggest this approach as a standard of care option.

To me this is fantastic paper. Until I heard the podcast, I didn’t know it existed. I don’t treat much GI disease so that is probably on me - but at the same time, searching Twitter shows zero results for “62” and anything rectal that I could find.

And therein lies the issue and why I opted to include the APBI example. This doesn’t align with the “narrative”. 28 fraction approaches aren’t deemed “cool” or “exciting”. But here, we achieve great results with dose escalation and a non-extended fractionation. And from my perspective, especially in light of RAPIDO, this study needs far more attention as we look to improve outcomes.

So I file this rectal dose escalation trial along side the FLAME SIB prostate data in ways - really great radiation focused approaches that are seeming to “loose” to shorter approaches which deliver less dose with likely inferior results.

We’re in a great spot in radiation oncology. Technology is letting us dose escalate and re-think some approaches that were limited by toxicity of adjacent tissues. I’m hoping we continue to let the pendulum swing back towards the center and we embrace some of these options as we look to improve cancer outcomes.

Looking ahead, I haven’t dug into the prostate high risk literature yet on this Substack. I trained at MD Anderson back in the day and we never treated pelvis with prostate cancer. I treat pelvis now sometimes but likely less than many. This review of EQD2 doses at 25/5 leads me to think we are mirroring similar issues in our pelvic short course approaches in high risk disease. But before typing, I need to go pull some references and read a while - high risk disease is a big bucket.

Thanks for reading.

If you wonder why my Twitter posts don’t have links here, Twitter and Substack and to a lesser degree LinkedIn seem to be at odds - if I add the links, less people see the posts - far less - so that is the reason - the algorithm at work. But as always, they should be pretty easy to find at:

www.protons101.com

Special thanks to both: Dr. Emma Holliday and Dr. Nina Sanford for getting great GI content out to the masses via their Twitter feed and podcast sessions, respectively. Well done.

REFERENCES:

Locoregional Failure During and After Short-course Radiotherapy followed by Chemotherapy and Surgery Compared to Long-course Chemoradiotherapy and Surgery - A Five-year Follow-up of the RAPIDO Trial

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36661037/The alfa and beta of tumours: a review of parameters of the linear-quadratic model, derived from clinical radiotherapy studies.

https://ro-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13014-018-1040-zPreoperative or postoperative irradiation in adenocarcinoma of the rectum: final treatment results of a randomized trial and an evaluation of late secondary effects

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8500374/Accelerated Partial-Breast Irradiation Compared With Whole-Breast Irradiation for Early Breast Cancer: Long-Term Results of the Randomized Phase III APBI-IMRT-Florence Trial

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.20.00650External beam accelerated partial breast irradiation versus whole breast irradiation after breast conserving surgery in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and node-negative breast cancer (RAPID): a randomised controlled trial https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32515-2/fulltext

Curative chemoradiation for low rectal cancer: Primary clinical outcomes from a multicenter phase II trial.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.17_suppl.LBA3514