Sunset Trial: Pushing Dose in Lung Cancer

How quickly and high can we go in Ultra-Central Disease?

Back in November, I wrote about Bob Timmerman and how he set the table for SBRT approaches in our field.

If you haven’t read it, I recommend it - nearly guaranteed to learn something relating to your SBRT practice - I did.

Here’s yet another example of the impact he has had. This time in helping define historical boundaries for when and where we can use SBRT in the treatment of central lung cancers. Below is a a paper back from 2006 that showed excessive toxicity with central disease when patients were treated with stereotactic approaches:

SBRT treatment dose was 60 to 66 Gy total in three fractions during 1 to 2 weeks.

Results: All 70 patients enrolled completed therapy as planned and median follow-up was 17.5 months. The 3-month major response rate was 60%. Kaplan-Meier local control at 2 years was 95%. Altogether, 28 patients have died as a result of cancer (n = 5), treatment (n = 6), or comorbid illnesses (n = 17). Median overall survival was 32.6 months and 2-year overall survival was 54.7%. Grade 3 to 5 toxicity occurred in a total of 14 patients. Among patients experiencing toxicity, the median time to observation was 10.5 months. Patients treated for tumors in the peripheral lung had 2-year freedom from severe toxicity of 83% compared with only 54% for patients with central tumors.

Nearly half the patients with central disease had severe toxicity. And that made us hit pause on pushing dose centrally for a good time.

Before we begin, Kudos to the authors of all of these trials - actively pushing to improve our science. Each of these takes a tremendous volume of work. Well done to all involved!!

The Broader Context:

Remember the broader context in lung cancer as well. We have this prospective, randomized 500+ patient study published in 2015 that showed no benefit to pushing dose with traditional dose (albeit with concurrent chemotherapy) in larger, more central generally node positive disease.

Interpretation

74 Gy radiation given in 2 Gy fractions with concurrent chemotherapy was not better than 60 Gy plus concurrent chemotherapy for patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer, and might be potentially harmful. Addition of cetuximab to concurrent chemoradiation and consolidation treatment provided no benefit in overall survival for these patients.

In fact, remember that the dose escalation group was significantly WORSE.

Median overall survival was 28·7 months (95% CI 24·1–36·9) for patients who received standard-dose radiotherapy and 20·3 months (17·7–25·0) for those who received high-dose radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] 1·38, 95% CI 1·09–1·76; p=0·004).

And in the treatment of esophageal cancer, we see the same thing - for that disease we run into issues at 50Gy. But regardless, we’ve tried for many years to escalate central chest disease and it isn’t always beneficial.

The Push Towards SBRT:

But these prior efforts haven’t deterred our push towards higher doses and shorter treatment approaches. My guess is the excellence in the peripheral disease of the lung and the continued improvement beyond lung - in things like renal cell or liver using SBRT “ablative” approaches - are just simply too strong of a lure to ignore.

So we ran RTOG 0813: Central tumors - not ultracentral and still found dose-limiting toxicity at 7.2%. But using a goal of dose limiting toxicity <20%, it did push the dose to 60 Gy delivered in 5 fractions.

Slowly pushing towards the center of the chest and continuing to push on dose.

But note that toxicity is still quite real - well over 5% even in this “central tumor” setting. Then came HILUS out of Europe..

HILUS Trial:

It was another push in this direction. It was a phase II multicenter trial for tumors less than 1 cm of the proximal bronchial tree. The SBRT was 7 Gy x 8 prescribed to 67% - so 83.5 Gy max point dose delivered in 8 fractions.

Grade 3 to 5 toxicity was noted in a large cohort - 22 of 65 patients including 10 cases of treatment related deaths - 10 Grade 5 toxicities. A crude rate of 15%. Wow.

And the trial has nuance - tons of details where the authors really demonstrated a very strong effort to balance toxicity - lots of give and take in the planning process - too much for this summary. In simple terms, they knew they were near the edge of toxicity limits and really tried to increase safety.

It was divided into 1cm or less from main bronchus / trachea (Group A) or beyond that region (Group B) - the red marks are the Grade 5 toxicities.

And despite the effort to limit toxicity, fatal events remained too high. The approach was not recommended in group A patients. Yet maybe… with additional caveats in group B, it was feasible. (again, when we choose to be supportive of shorter approaches, we are quite supportive).

Which brings us to the most recent results in this area of our field.

The SUNSET Trial

SUNSET Trial - presented the end of November continues this push towards dose and shorter fractionation.

A Phase I trial enrolling T1-T3 node negative only patients in “Ultra-central location” - defined as PTV touching the proximal bronchial tree, pulmonary artery or vein and / or esophagus. No endobronchial invasion (a previously identified risk factor for Gr5 toxicity - ie death) was allowed but bronchoscopy was not required.

The original trial proposed pushing doses higher, but following RTOG 0813, the “highest” dose arm was 60 Gy in 8 fractions with two options to de-escalated if needed.

For planning - contrast was required for the simulation. Full proximal bronchial tree was outlined. 5mm PTV margin and hot spot no more than 120% (so relatively uniform dosing). Note: More cautious. Lower hot spot. Smaller margins. Larger zone of contouring the proximal bronchial tree.

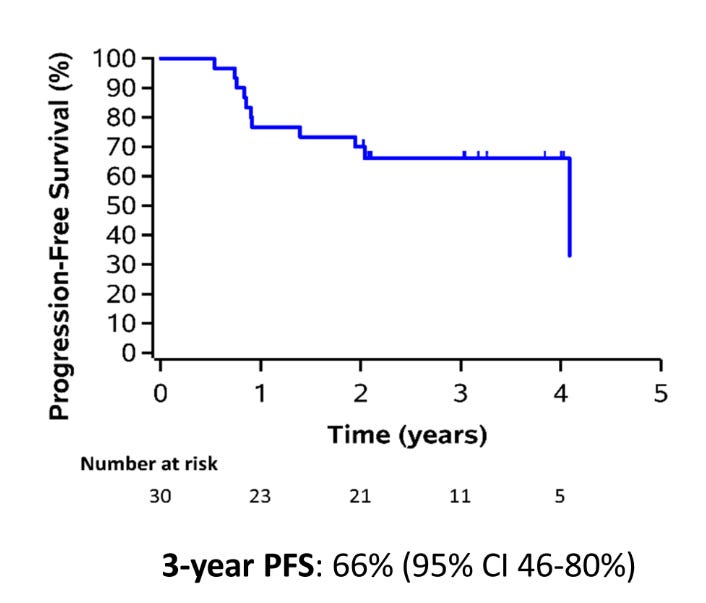

The entirety of the trial is 30 patients - so it remains a very small cohort. Progression free survival is shown below at 66% at 3 years.

The Grade 3-5 toxicity rate was 6.7% with a Grade 5 toxicity of 3.3%.

The conclusions:

we conclude that 60 Gy in 8 is safe to use in clinical practice.

My Commentary:

Just because you CAN do something, doesn’t mean it is the ideal path.

When the goal is shorter, we are certainly willing to accept some toxicity risk. From my perspective, I still view these toxicity levels as quite significant. It’s an important trial and continues to define the edge of tolerance in the lung for what one can do and what one should not do - again, well done. But for me? I’d much prefer exploring safer approaches - something like 60-70 Gy in 10 or 15 fractions and incorporating immunotherapy / chemotherapy into the planned approach - I think that approach today has more upside than a bit more dose or a few less fractions.

And really, that is my main question. Why such a continued push to take such risks in more and more central disease when we know that 1) concurrent chemotherapy can really help with outcomes in more advanced disease and 2) immunotherapy / targeted therapy is likely replacing concurrent chemotherapy for many in this setting. Heck, even in true early peripheral disease, immunotherapy is making a strong push as a beneficial addition.

I listened to the associated ASTRO Podcast and they discussed what might contribute to the toxicity and it really emphasizes just how razor thin the line is between a good outcome and and a really bad one.

Blood thinners, and biopsies were mentioned - need to be careful. They talked about carboplatin or cisplatin as risk factors weeks or maybe months following treatment as they can affect blood counts. Remember the toxicity we are trying to avoid is a fatal bronchial hemorrhage. I’ve seen one in my career - don’t want to ever see another.

But consider the following scenario. You treat a patient to this type of dose and then later - maybe weeks or a month later, your patient is admitted at some different hospital via ambulance. Physicians who are far less aware of the patient’s detailed history begin interventions which might then carries a real risk of death due to the damage of the SBRT - say a blood thinner that might or might not be truly “required”. And you likely aren’t even aware of admission. If that is plausible, then is this really the best initial approach? I think it is, at least, a reasonable question to consider.

Add in the uncertainty from site to site noted in this recent publication and you would appear to have some real risk.

To me, the more critical question is not how high and how quick we can ONLY give solo therapy with radiation, but rather, how we can high dose treatment with other approaches - primarily in todays world - immunotherapy.

Which was exactly the approach in this study by Dr. Chang from MD Anderson.

A Major Synergistic Win In Lung Cancer!! High Dose Radiation Plus Immunotherapy:

Another week - another great radiation outcome for cancer patients!! Today, we’ll just begin with a pretty impressive curve out of a study from MD Anderson. This is event free survival after initial treatment for “early” lung cancers. And it demonstrates a big win if you combine immunotherapy and SABR radiation.

In that trial, the concurrent treatment with an immunotherapy increased the event free survival from 53% to 77% - at 4 years. So in a comparison to our current trial, an extra year out, 10% higher. Which begs the question of - how much is the extra dose really adding. It’s not easy to say definitively. We know that the closer to ultracentral the tumor is located, the higher the nodal risk and the higher the metastatic risk so these are different cohorts with different risks.

But in the Chang trial they also were quick to use 70Gy in 10 fractions for central lesions - ultra-central lesions were excluded. And while there were very limited numbers of patients in the 70 Gy treatment cohort, the data suggests a similar strong benefit on subgroup analysis.

And then consider, in this earlier report of the SUNSET trial, there really isn’t a difference between central and ultra-central with respect to survival. Maybe a little better but there isn’t a clear large scale improvement. Clearly we can push the dose a bit more the more peripheral the tumor becomes, but if immunotherapy can move the event free survival curve in a large scale fashion - creating HALF the failures - how hard should we really push if the risk is Grade 5 toxicity.

Final Thoughts:

I believe in radiation and I believe in dose. I think the older lung data that showed no benefit to dose escalation is likely toxicity related but I think it still carries a lot of weight and importance. When my mother in-law was diagnosed with IIIB NSCLC, I pushed pretty darn hard to get her concurrent treatment. She made it over 5 years. I’m pretty sure that was a better path than neoadjuvant chemotherapy (which was recommended) or just pushing on dose. I know those are apples and oranges, but I often defer to broad context. And the broad context makes me think that there is some real benefit in most of these case (if not all) for something systemic.

As I wrote on X, consider just how far this approach is to what we pursue in prostate cancer. In prostate cancer, we have some in leadership arguing in favor of diagnostics to predict ADT benefit in a disease setting where 96% of patients are cured. We are so very, very far from that level of excellence in lung cancer - especially in central disease. And so, considering the larger picture, I’d be more enthusiastic with integrated approaches that demonstrate wider safety margins, and yes that means a few more fractions.

What if, rather than pushing so very hard on dose and fractionation, we softened the radiation aspect and integrated immunotherapy consistent with the Chang MDACC approach. Or look at this new approach with primary nodal drainage coverage. Certainly a few extra fractions gives us more safety to explore each of these “common sense” (my words) approaches as we enter ultra-central disease.

What if we started at 60-70 in 15 fractions for ultra-central disease and we moved to 12, then 10, then 8, and then maybe to 5 as we learned. Maybe that takes a few years or even a decade, but I’m not sure we have “lost” anything. In fact, I wonder if that type of integrated approach for this disease doesn’t make more sense than pushing on the singular radiation pedal harder and faster.

And to be clear, most data today likely argues for immunotherapy in a sequential approach. The Chang data is somewhat of an outlier in that respect, but I think the goal is to integrate systemic and ablative type dosing schedules with maximum safety. And today, we can’t even seem to figure if the immunotherapy should be concurrent or adjuvant. Or if the radiation is best given as “high dose ablative” or “low dose radscopal” (REF). In that setting, I’m not convinced defining dose at the razor’s edge is prudent.

I appreciate the work and effort in the trial. Anytime a radiation trial gets positive press and reception I applaud - often quite loudly. But here I applaud with caution. In the end, this a small patient cohort with significant and persistent risks of high grade toxicity. While I think it is a very valuable study in helping to demonstrate what is important and what is less so, central disease remains a site where we have literally tried for decades to increase dose without clear success. I struggle to accept increases in toxicity while other approaches - like the integration of immunotherapy and or chemotherapy appear to demonstrate more robust changes in outcomes - not just reasonable safety profiles.

Addendum: A New Study lands!!

I wrote this piece back in December asking for longer integrated approaches for more central disease - and then just this week, this paper lands:

X-Thread: (strong summary thread - highly recommended).

Briefly - it worked - it’s small with only 28 patients but they gave 15 fractions concurrently with chemo with good success. Here are some quotes from the paper:

“All patients received 4 Gy x 10 treatments followed an adaptive SABR boost to residual metabolically active disease consisting of an additional 25 Gy (low 5 Gy x 5), 30 Gy (intermediate, 6 Gy x 5), or 35 Gy (high, 7 Gy x 5) with chemo. Total doses: 65-75 Gy in 15 treatments”

“MTD was not exceeded. Non-heme acute and late grade 3+ toxicities were 11% and 7%, respectively. No grade 3+ toxicities were seen in the intermediate-dose boost cohort. Two deaths in the high-dose boost cohort.”

“We think that this regimen holds promise as a new backbone for #chemoradiation that utilizes adaptive SABR to 70 Gy in 15 treatments with chemo as it appears to be very effective and safe.”

There’s too much in it for me to add full coverage, but it appears my crazy idea wasn’t that far off. Of note, they did it via a more clever approach than I proposed with different fraction sizes at different times, but still… every once in a while, you get lucky. Kudos to the authors in pulling off a great trial within a unique and novel dose escalation approach. Well done!!

And with that, we have TWO “little bit longer, not really SBRT approaches” that, in my assessment, should be taking center stage for ultra-central and node positive lung cancer.

If you made it here, please hit the like button or leave a comment so that others can find the content. Next up, a look at a billing oriented paper that I believe missed the mark.