PSA Screening: Data Speaks Loudly

Recommendations changed in 2012 and outcomes immediately worsened. What the data shows and how we can do better.

Quick Background:

I’ve treated prostate cancer for some 20+ years. From the original MD Anderson dose escalation toxicity data, to implants back in the 90s, to a center that treats around 400 men per year with prostate cancer - prostate cancer has been an area of interest. And in the last half decade I worked a lot on PSA kinetics (both pre-treatment and post-treatment) - an area where I’ve spent far too many hours :).

So following the announcement of President Biden having metastatic prostate cancer, the last few weeks have been disappointing with respect to the quality of information on the topic of screening and diagnosis - so much of what I’ve seen on TV or read has been not great (as nice as I can be). Today I’ll put down some thoughts and try to explain where we are, where we came from, and mainly focus on why I think PSA screening recommendations in the US are inadequate.

First off - hats off to Daniel Spratt, MD - he is no doubt an international prostate cancer expert from within the field of radiation oncology. He did a wonderful job framing the discussion and his X-torial was the inspiration here. Many points below come from his post on X - some I even copied directly as they were so precise, I couldn’t improve them. (I mark these quotes with a *). He is going to sit on the NCCN panel for GU and I think will help to steer it in a correct direction.

But today, I’m getting patient questions daily, and I want an easy reference source for my thoughts. This will be that article. Hopefully it helps others - it will certainly help me clarify / recall my thinking.

Prostate Cancer is an Important Cause of Death

While prostate cancer is often indolent and slow growing - it is not always. It remains the #2 cause of cancer death in men. Below are SEER data from the NIH.

I highlight three facts. They all will contribute to my conclusions and to the history of the US recommendations on screening.

First, it is by far the most cancer diagnosis in men. Essentially 3x lung and over 3.5x colon and rectum.

Second, it is responsible for the second most deaths - more than many “deadlier” cancers due to its prevalence in the population.

Third, the relative survival is far and away the best. Next best in the list of the top 10 is bladder at 80% - nearly 10x the relative death rate of prostate cancer.

These three simple facts will frame our discussion - it is a common disease with excellent survival, yet still a large driver of cancer deaths in men.

A Look Back:

PSA screening (a simple lab test) began more broadly in the early 1990s. In 1996, I started in training. At that time we still saw the older disease from the pre-PSA era and were seeing the newer ones found using PSA - with far less disease in the prostate. I saw both and PSA literally changed the volume of disease that we saw at presentation - rapidly.

But momentum swings. Based on appropriate concerns over too much treatment in low risk disease and too many procedures following elevated PSAs, we officially moved against PSA screening. In 2012 the U.S Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) made a controversial recommendation against PSA screening, irrespective of age.

In simple terms, we threw the baby out with the bathwater. PSA screening (in my opinion) wasn’t and isn’t the problem. The problem was doing too many downstream actions based on a screening lab that resulted in too many procedures and too many men getting treatment.

Many prostate cancer societies & experts opposed these recommendations. Unfortunately, as Dr. Spratt pointed out, the Chair and Vice Chairs of the 2012 USPSTF were not prostate cancer specialists:

Chair: Area of Expertise: Pediatrics, preventive medicine, evidence-based medicine, and clinical guideline development.

Vice Chairs (2012):

Area of Expertise: Family medicine, primary care, preventive medicine, and clinical guideline development.

Area of Expertise: Geriatrics, internal medicine, health services research, and evidence-based medicine.

Certainly hindsight is nearly perfect and all three had “expertise” in preventative medicine or guideline development, but in retrospect, they were not prostate cancer experts and they missed. And data proved them to be wrong. And quickly - which is quite difficult to accomplish in prostate cancer.

***If you got here, leave a comment, like or share. Content here is free but these small things really do help.***

From Better to Worse: Guidelines Impact Outcomes

Prior to this shift, less men were dying from prostate cancer. Year over year - fewer and fewer men per 100,000 men died. Almost immediately this trend broke. Age-adjusted rates of prostate cancer specific mortality went from declining to flat.

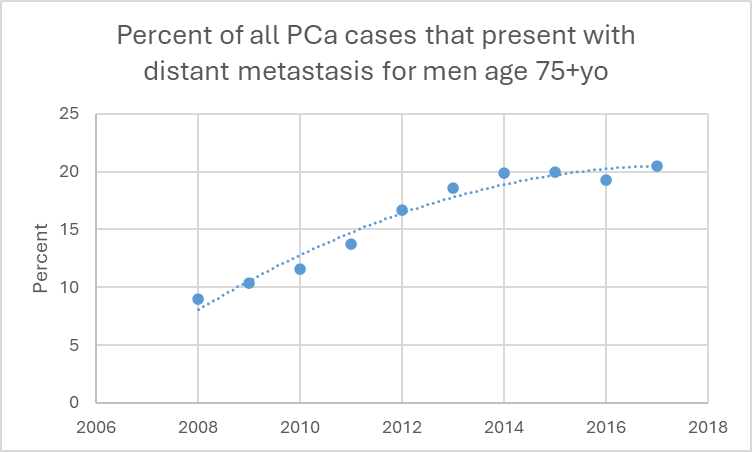

And metastatic disease at presentation - like we just witnessed in President Biden, jumped especially in older cohorts of men. Below is a graph showing just how quickly this single recommendation changed the presentation of this disease.

(REF for graphs)

As a clinician in the field, you saw the shift. It was obvious. PSA weren’t drawn and we saw more advanced disease. The recommendations were clearly wrong and just 6 years later, they were partially reversed.

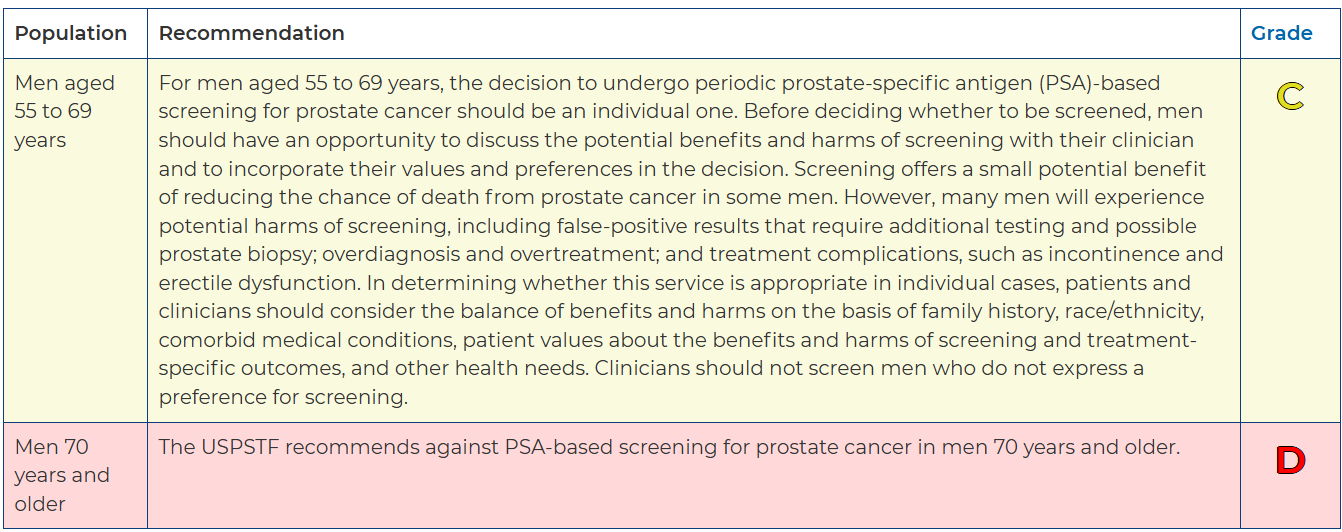

Here is where we are today. The current 2018 U.S Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against PSA screening in men >70 yo. Again, many prostate cancer focused academic/scientific societies disagree with USPSTF but here are the current guidelines.

From my perspective, it was 1) an acknowledgement they were incorrect, but 2) still trying to rationalize their poor prior decision and “prove” the 2012 recommendations were “kind of” justified.

(To be clear, I disagree with both - C and D recommendations. I believe we should have a general population trend towards integration of routine PSA draws assuming good health).

The thinking is (on some level): older men have greater competing risks so worry about screening for prostate cancer less. The sicker / closer to death people are, the less screening makes sense.

But look at this data from the ProtecT trial - 10 yr report published in 2016 - Nearly all the deaths from prostate cancer occurred in men over 65.*

Similarly, in RTOG 9408 (a randomized trial of men with low to high risk prostate cancer), men >70 yo were twice as likely to die of prostate cancer than men <70 yo (10% vs 5%) after radiotherapy. That is despite older men being at higher risk of dying of other causes.*

So while it might make some sense broadly in “screening theory” to be more cautious in this older subset of men - here we have two prospective bodies of evidence saying there is real risk in not screening this cohort.

Many articles and experts stated, metastatic disease at presentation, like what Joe Biden has, just doesn’t happen. That is incorrect. Rates since the shift in 2012 have been clearly rising. Below is the percent of men over 75 presenting with either nodal disease or metastatic disease. As you see, clear trends higher since 2012.

To show the difference in the rate of presentation with metastatic disease by age: (Seer database: Ref 1, Ref 2)

<50yo: 0.25 per 100,000

50-64yo: 15 per 100,000

>75yo: 110 per 100,000

The incidence of presenting with metastatic disease at diagnosis is ~400x more likely in older men than young men.

So while it IS rare in young men, it is happening far too often in men over 75. Unfortunately the President’s diagnosis is consistent with the data. Many “experts” in the media appear to not understand this dichotomy.

Here is another of view of the change in older men presenting with metastatic disease. As you can see in this figure, today about 1 in 5 men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 75+yo are diagnosed with distant metastatic disease. This used to be 1 in 14 men in 2008.*

If you look at the totality of the data - the trends are clear. Less screening has worsened real and obvious metrics for prostate cancer. And the number of “experts” that know this data are apparently far less than I would expect.

While men who are 75 are, of course at higher risk of dying from something other than prostate cancer, using social security data, ~1 in 4 men that are 75 years old will live until 90 years old or older. Given such a high percentage of older men present with regional or distant metastatic disease, you are putting a lot of men at risk by not continuing screening into their 70s.*

Summary According to Dr. Spratt:

President Biden’s physician followed the current USPSTF recommendation to not perform PSA screening in men >70yo. However, the USPSTF recommendations are flawed as prostate cancer is common in men >70yo. In that group of men it is often more aggressive and if untreated men, are more likely to die of prostate cancer. Focus should be on increased PSA screening, but reductions in over diagnosis and over treatment.*

Improving “what happens next”.

A PSA blood drawn isn’t the problem. The algorithm for “what happens next” is where the work needs to be done.

I can hear Vinay Prasad saying that PSAs don’t improve overall survival and that we treat far too many early men or do way too many biopsies. All of that is true. But prostate cancer specific deaths were clearly falling (see above) and undoing the screening clearly altered this decreasing trend. It also is evident in the number of men presenting with metastatic disease. These are both important clinical outcomes. It isn’t randomized data, but here in this singular instance, it is likely even stronger evidence for the value of screening. The data are simply that clear.

And realistically, we have made tremendous progress since the data back in the early 2000’s.

First, we observe and follow more cases without treatment.

When I started training - most low risk disease was treated - in fact only about 10%-20% was managed conservatively. Today this number is anticipated to be about 75% of low risk disease will be managed conservatively.

We have run great trials (like the ProtecT trial out of the UK) that demonstrate very low risks with not treating low risk disease and have made that approach more acceptable.

Secondly, we have better tools.

Back in the day, we didn’t have many great options beyond moving towards biopsy. But today we even have a number of blood / urine tests to help determine who really even needs biopsies. Here are the current NCCN supported tools available prior to biopsy:

Prostate Health Index

SelectMDx

4kscore

ExoDx Prostate Test

MyProstateScore

IsoPSA

Beyond these pre-biopsy tools, we have multiparametric MRI to look for disease, and if we decide to biopsy. Post-biopsy there are genomic tools to help steer additional patients towards active surveillance beyond the classic three of 1) Exam, 2) PSA, and 3) Gleason score.

Finally, we’ve moved towards some common sense.

For 20+ years my simple rule has been:

Take your age, divide by 10.

If your PSA is higher than that, it likely warrants evaluation.

This summary from 2023 comes about as close as I’ve seen to mimicking my rule in print - using higher ranges as people age:

40 to 49 years: 0 to 2.5 ng/mL

50 to 59 years: 0 to 3.5 ng/mL

60 to 69 years: 0 to 4.5 ng/mL

70 to 79 years: 0 to 6.5 ng/mL

Note - I’m more cautious in taking action than even this recommendation. I believe my rule is much easier to remember / apply sitting in front of a patient. It won’t be perfect - PSA isn’t perfect, but in 20 years this works really very well.

PHI and the other tools above will almost certainly outperform this type of approach, but I think this shows an easy to remember way to frame discussions with patients.

Better but Still Too Aggressive

So generally, we have moved significantly in a more cautious direction. But we still are too aggressive in my assessment. In my article from 2 years ago, I highlight differences in the US vs. the UK approach.

Here was my example written back in 2023:

The UK and US are very different markets - below we compare and contrast the path of a low risk patient on the ProtecT trial to US NCCN Guideline medicine.

Both are biopsied in 2016 - PSA of 6 - GG1 disease. Today, PSA is 19. A slow patterned rise.

ProtecT:

Lab only - not even a doctor visit.

US NCCN Version:

MRI in early 2017.

Confirmatory Re-biopsy in late 2017 - required.

Annual MRIs because of rising PSAs

2019 - 3rd biopsy of prostate - periodic biopsies recommended for most men.

2019 - Oncotype due to availability and no prior genetic testing. Still low risk disease.

2022 - 4th biopsy - PSA now above 15 and suppose MRI showed enlargement of lesion.

2023 - recommending 5th biopsy as PSA approaching 20.

I want to emphasize the above is COMPLELELY consistent with our NCCN guidelines. It forces men to have treatment in ways. If we want active monitoring to be an option, we have to fix the guidelines.

It is unlikely that much beyond ProtecT accomplishes anything that is clinically important and almost certainly it contributes to risk / toxicity.

Again, the PSA isn’t the issue. The issue is the downstream stress and costs and infection risks from all these additional steps. Instead of stopping the “risk free” blood test - we need to fix the downstream ramifications in our medical-legal system of healthcare.

Summary: Let’s use this event to move forward

Back in the day, we had limited options. Today we have numerous steps post-PSA and pre-biopsy to help frame risks. We have MRI to help limit biopsies and genomics on the biopsy to guide treatment. We understand low risk disease can simply be watched. So many things that were not available previously.

And in the case of President Biden, it is almost “free”. He clearly has - at least - annual blood draws. There is literally no risk to the information aside from bad decision making / discussion post lab. Well to be precise, there is “some” ultimate risk because there will be false positives, but we quadruple the risk by making the “Active Surveillance” NCCN pathway so regimented. The answer is to loosen the re-biopsy and MRI requirements so that we can draw PSAs more often with less over-biopsy and less over-treatment.

Ultimately PSA is very good at avoiding metastatic diagnosis of prostate cancer - not perfect, but really good. From the numbers before, the general population age 75 and older moved from 1 in 14 risk to 1 in 5 risk. For the screened population the effect would be greater - so more than a 3 to even 5 fold reduction in metastatic risk is quite plausible.

To me, I’m hopeful that this high profile case illustrates issues with our screening recommendations and it can bring to the forefront that we still over emphasize invasive procedures following PSA screening in the NCCN algorithms. Those are my thoughts and why I personally will deviate from the “standards” with myself, my friends and my family. Too much risk in seeing the #2 cause of cancer deaths in men being found too late to not have a simple blood test.

And population data supports my thinking. Let’s keep pushing for better.

Can you please explain the rule-of-thumb that you've been using for 20 years. (Take your age. Divide your PSA by 10. If your PSA is higher than that, it likely warrants evaluation.)

I'm unclear about the parameters and the calculations. Let's take a specific example from my own record when I was 65, and my PSA was 10.47.

So I divide my PSA by 10 to give 1.047. You say "if your PSA is higher than that". What specifically is "that"? I'm completely confused! Shouldn't I be multiplying my PSA by 10, or dividing my age by 10?

That said, I totally agree with your views on PSA monitoring. I was stunned on hearing Biden's diagnosis, a condition that could have been so easily avoided if he'd undergone regular PSA testing,

In the ProScreen trial only 2.7% of the men screened with a PSA had a biopsy!JAMA Net 4/6/24 (positive 4K and mpMRI)

Of 15 201 eligible males invited to undergo screening, 7744 (51%) participated. Among them, 32 low-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.41%) and 128 high-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 1.65%) were detected, with 1 cancer grade group result missing. Among the 7457 invited men (49%) who refused participation, 7 low-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.1%) and 44 high-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.6%) were detected, with 7 cancer grade groups missing. For the entire invited screening group, 39 low-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.26%) and 172 high-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 1.13%) were detected. During a median follow-up of 3.2 years, in the group not invited to undergo screening, 65 low-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.14%) and 282 high-grade prostate cancers (cumulative incidence, 0.62%) were detected. The risk difference for the entire group randomized to the screening invitation vs the control group was 0.11% (95% CI, 0.03%-0.20%) for low-grade and 0.51% (95% CI, 0.33%-0.70%) for high-grade cancer.

Not only that but microUS is a much cheaper screening tool than an mpMRI. It is proving to be just as effective.