My End of Year Review of the Proton Literature noted just how strong this article was placing it at number 2 on the “best of” list for 2023:

Today, we’ll look a bit closer at this study and link up one additional publication that continue to show support for the idea of using protons in the treatment of lung cancer to decrease toxicity and improve outcomes. And yes, “new” randomized data is on the way which absolutely is required for this site.

Article One: The Backdrop

Prediction of Pulmonary Toxicity

We’ll use this article as supporting evidence to set the stage.

After all, we are in an area where there is a randomized trial from 2018 that shows no benefit to proton therapy. There are issues with that older trial that you can pick at from the proton support camp, but the trial was designed to show benefit and did not - in fact, it trends the WRONG way with a Gr3 toxicity hazard rate of ~1.35 for protons compared to IMRT.

But this new article gets to really one of the main issues with the older MDACC randomized data - it was passive scanning. I’ll explain:

Passive Scanning vs. Pencil Beam: 3D vs. IMRT

How Things Work:

In passive scanning approaches you have really one option - you shape and conform the distal beam edge to the distal shape / contour of the target. You set a range (or “depth”) and you set a mod / modulation (the distance of the SOBP). In the picture below, “range” would be ~28 and mod would be ~13.

This results in the following moving from 2D to 3D:

If the top part of the PTV is 6 cm from front to back and the middle portion is 13 cm - your mod has to 13 cm. The typical approach is to shift the end of the beam to the tumor and adjust its shape (with the compensation) but in passive approaches these are fixed per beam (at least in our setup). This results in: at the top of the tumor where it is thin, you will have 7 cm extra of treated high dose proximal to the tumor

This is fundamentally why the choice of beam arrangement is just so critical in passive scanning - it isn’t just what you are traversing (avoiding big differences in effective depth due to densities) but it also relates to the consistency in the treated length along the beam axis of the target from a depth perspective.

Since IMRT, this is not applicable to photon planning. The best examples in photons might be 1) the excess dose in an AP/PA plan anterior and / or posterior to your target or 2) a single beam plan for a spine.

On the other hand just like with IMRT, pencil beam gets rid of this concern. There can be some other factors to consider relative to photons with robustness and effective depth / density differences concerns that are more sensitive with protons, but the target size can be readily adapted.

This is really why the older esophageal trial showing significant toxicity improvements is about two steps stronger than most appreciate - it was essentially passive scanning compared to modern IMRT (80% were passive scanning) - and it still won - quite easily.

This article seeks to address this difference. Here we look at the difference between passive scanning approaches and pencil beam approaches and use modeling to predict pulmonary toxicity.

So clearly, this paper isn’t perfect - it is using a database that is far from ideal - really you can say that for anything retrospective in nature. And then it models. And then ironically, it largely is forced to use photon data, because that is where most patients get treated and therefore where most toxicity data will lie. But it is consecutive patients using pretty sophisticated modeling to predict pulmonary toxicity. And it has good representation of both passive scanning and pencil beam approaches.

Essentially this study attempts to “measure” the extra dose effects I just described.

A Quick Aside:

As soon as this article landed I saw a quote arguing that passive scanning should never then be used for lung cancer - which isn’t quite what this trial addresses. Me, being quite cynical at times, thought of this old “first” principle of proton therapy:

Physician “displeasure” with protons is inversely proportional to the distance from their competing center to the nearest proton center squared. And then because it is X (formally Twitter), times c.

And I’ll just say, it checked out.

I agree it likely isn’t the best place for them, but the older trial was pretty even for outcomes once through the initial learning curve and then the subsequent UPENN concurrent Baumann data is quite favorable showing protons are possibly superior in high risk patients, but my more global point is this:

Until we address this division on some level and start cooperative arrangements between institutions with and without protons (or MRI linacs) or whatever high end capital - we will have large issues if / when technology is shown beneficial.

It is one of the more critical issues facing our field today from my perspective. Institutions have built incredibly high walls to keep cases “in house” that can be detrimental to care. Each quarter, ask yourself, any referrals beyond your walls? Either for expertise on the care side or convenience for the patient side? From treatment, to imaging, to labs… just consider.

Ultimately this current paper lands with the following conclusion: a significant reduction in pneumonitis with the jump to pencil beam demonstrated in a prospective dataset:

This study is the first based on prospective data to demonstrate that treating patients with PBS is associated with a lower probability of radiation-induced pneumonia/dyspnea (0.08 vs. 0.34, p = 4.54e-07 ) compared with the use of other (e.g. passive or double scattering) techniques.

Again, this confirms that what we see on plans - ie dosimetry - translates to outcomes. We believe it here quite readily because it speaks to problems with older proton approaches, but it also speaks to the real chance that protons can and will outperform photons in many cases moving forward.

The Main Event: Lymphopenia Reduction

This is an important trial out of Italy and the Netherlands published in November 2023. It has a few notable strengths. It is a retrospective review, but it is data that was prospectively collected on a series of consecutive lung cancer patients treated with IMRT (specifically VMAT) or proton therapy (specifically IMPT). (So a true modern approach evaluation).

Importantly, these are patients in which normal tissue complication probability models predicted benefit for proton therapy.

In all centers, patients were selected for receiving IMPT through Normal Tissue Complication Probability (NTCP) models. These models predict the expected benefit of IMPT compared to IMRT.

From the Supplemental data - specifically, here are the four criteria:

Reduction of grade ≥2 pneumonitis by 10%

Reduction of grade ≥2 esophagitis by 10%

Reduction of all-cause mortality at 2 years by at least 2%

Reduction in the sum of esophagitis and pneumonitis grade ≥2 by 15%

So, in simple terms, to qualify for protons, you needed to be high risk meeting one of the above criteria. The study then evaluates 71 proton patients, and 200 IMRT patients - consecutive, prospectively enrolled cases. All cases treated to 60Gy-66Gy in 25-30 fractions along with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy.

Dosimetry is different as one might expect, but notably much more different than in the MD Anderson lung trial - again, we’re removing a large part of un-needed dose with the shift to IMPT. Per this study, protons are markedly better for protection of dose from the bone marrow, lungs, heart, and body.

For easy comparison, here is the mean lung dose from the MD Anderson lung trial. Before no different, and now they appear quite different. (p=0.06 - but visually one is better, one is worse)

The trial finds significant reductions in toxicity with the use of proton therapy.

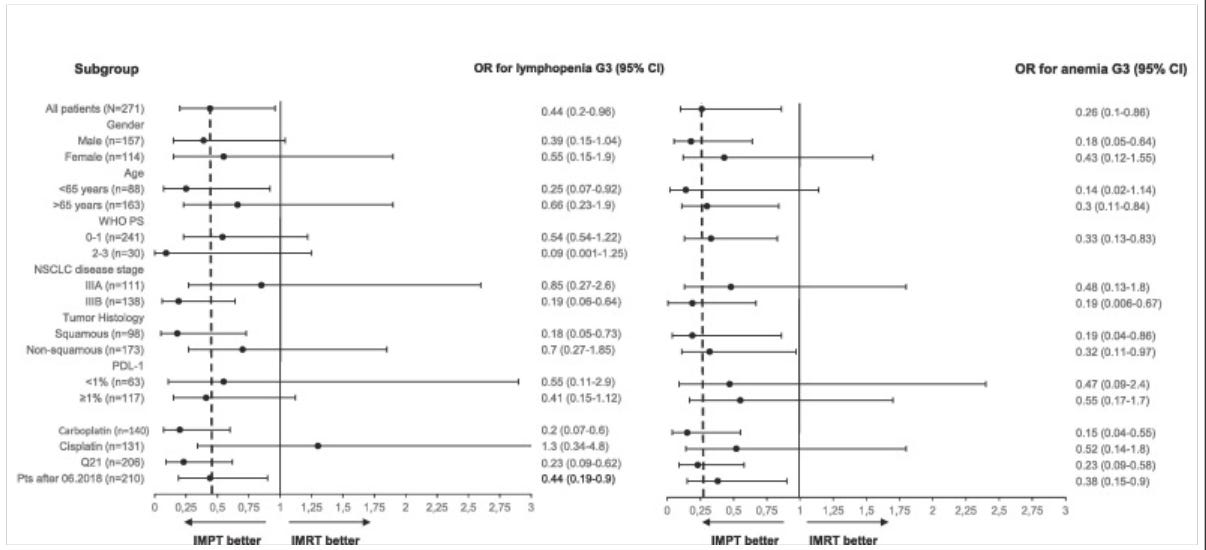

The incidence of lymphopenia grade ≥ 3 during CCRT was 67 % and 47 % in the IMRT and IMPT group, respectively (OR 2.2, 95 % CI: 1.0–4.9, P = 0.03). The incidence of anemia grade ≥ 3 during CCRT was 26 % and 9 % in the IMRT and IMPT group respectively (OR = 4.9, 95 % CI: 1.9–12.6, P = 0.001). IMPT was associated with a lower rate of Performance Status (PS) ≥ 2 at day 21 and 42 after CCRT (13 % vs. 26 %, P = 0.04, and 24 % vs. 39 %, P = 0.02). Patients treated with IMPT had a higher probability of receiving adjuvant durvalumab (74 % vs. 52 %, OR 0.35, 95 % CI: 0.16–0.79, P = 0.01).

The results really are not that close. Yes, many touch or include equivalent outcomes, but in simple terms, if you were picking your treatment - photons or protons, you would pick protons.

So protons won with:

Less Lymphopenia

Less Anemia

Better Maintenance of Performance Status

Greater ability to get Immunotherapy

Selection “Anti-Bias”:

A note on selection bias. Clearly here, we are modeling for benefit - trying to model which patients might benefit the most from proton therapy but I think this part of the discussion is quite critical to consider:

The selection of patients trough NCTP models, introduces a selection bias. However, the selection bias in our population worked against the IMPT arm since the patients who received IMPT were the ones expected to have greater toxicity.

So while selection bias may be a significant confounder that might lead to significant bias in the results, here - it really might not. The patients selected for benefit should do worse, yet did better.

My Comments:

Pairing these two studies together, I think you get a pretty powerful argument that we are quickly closing in on being able to:

Demonstrate that some lung cancer patients really do show improvement of outcomes with modern proton therapy relative to photon VMAT approaches.

We are able to model and effectively parse a broad population of lung cancer patients - choosing those who will see benefit.

And this study was NOT overly specific. In this study about 1 in 4 patients (26%) were selected for benefit with proton therapy. In reality, these results argue for benefit in a large scale populations of lung cancer patients.

PROton DOSimetry Comparison Concept:

I’ve been arguing for quite a while that this should be our approach. We must use dosimetry paired with modeling to perform appropriate selections. I first wrote about this back in 2019 - within a year of showing up here in Oklahoma City.

It’s my whole PRODOSC project. The idea was “PROton DOSimetry Comparison” Trial.

Here is a link to OAR dosimetry metrics:

Specifically, it documents my rationale for the inclusion of these 15 metrics. It’s a 9 pg document with about 3-4 references per structure which describe the strength of the metric and the

Of note, I have no doubt this work could be improved - but it was my solo attempt - based on 2019 work so now quite old in today’s rapidly changing world.

Regardless, this current lung trial ultimately choose 1 in 4 lung patients as “likely to benefit” from treatment with protons AND it appears to have worked.

And on an exciting note, something along the lines of my PRODOSC trial concept is now in the works nationally - it is a different, yet similar, approach. I think it is cleaner than my vision and I’m happy to be helping to try to get the project over the finish line. If it works out, we’ll have a phase III trial looking at this type of broad proton use case scenario - we shall see. Hopefully more details to follow…

Conclusions:

In the end, I believe this is where we must end up. Attempting to select and utilize protons for the instances where they provide the most benefit. I believe we’ll need really good dosimetry metrics and modeling to help point us in the correct direction. And we will have to be cooperative as a specialty for our collective patients to see the most benefit. Simply there is a lot of work to do.

It will always be a moving bar. Photons will improve. Protons will improve. The potential for differences between the two may lessen or become greater with time - I think there is real potential for either of those two answers to be the case. I think it is likely that the improvements we see on the photon world will close any potential gap for many high volume common use case scenarios, but not all.

I still think, moving out a decade, it will be clear that there are cases and times where the physical property differences between the two approaches will be maximized by clinicians and that we will figure out when and where there is benefit. I guess I’m just optimistic by nature. But I’ll give a quick example for a case that today, I do not think there is good enough data to consistently support protons - a medial left breast cancer in a young patient - say 40s.

The photon plan is solid - total mean heart dose of around 2 Gy including the operative bed boost but the proton option is closer to 0.35Gy. Both are “well within standards” but clearly there is no reason for dose in the heart. If costs and complexity trend towards similar factors of scale and we get better at documenting heart effects from treatment, even this case will become difficult to justify the extra dose - at least that is my perspective.

But to get there, we’ll need good trials and we will need to be critical in our assessment of the data. When things don’t work, we need to be up front and acknowledge those issues, just like in the old lung trial. The better and more accurately we assess the data and all possible rationales for the outcomes, the quicker we can make the shift towards better outcomes. And if we prove the benefits to the platform, then we must mandate cost, efficiency improvements for those beneficial platforms. End of the day, we are clinicians and our goals need to be to optimize patient outcomes.

I’ll close with this update showing just how far we have to go: RTOG 1304 closed to accrual last year in September (article). It is the national randomized trial looking once again at photon vs. proton treatment for lung cancer.

But honestly, it struggled to accrue. Nearly 10 years to reach accrual and likely 2-3 years of development. So the concept for the trial was back in 2012? or so. Maybe we get answers in the upcoming year but as technology moves faster and faster, we have to develop ways in which our small field can do better than to answer such a critical question in a time span of much less than 10-15 years.

330 lung cancer patients: 10-15 years. Many won’t have been treated with VMAT. Many will have passive scanning proton approaches. Stage II disease that might be best served with SBRT approaches today are likely included. And that is why I choose to include the quick aside about protons and unification of our small specialty. We’re better off if we can move to consolidate and unify our field to answer these basic issues than we are if we choose to claim that others are the problem.

We judge ourselves by our intentions, others by their actions. – Unknown

Just a thought - but 330 patients taking a decade. I believe we can do better.

I’m biased. I think the answer will lie within “what percentage of cases” benefit rather than “is there any benefit”, but time and data will tell. And the answer likely will be not as clear as the headlines - it will be more in a region of gray. And therefore it lands on us to read and evaluate and think and translate that information to our patients and their families.

As always, thanks for reading along. If you learned something or even might consider a different perspective, please hit the like button or pass it along - it is how the world works these days.

Additional References:

Cardiovascular Substructure Dose and Cardiac Events following Proton- and Photon-Based Chemoradiotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37408679/