Head and Neck Cancer Radiation: The Risk of De-Escalation - When is it a bridge too far?

A recent trial demonstrated 5 of 19 people failing initial head and neck cancer treatment for HPV+ disease within 3 months which I think raises questions.

www.protons101.com

Home to the musings of a radiation oncologist - with a slant on protons and dose and optimizing cancer outcomes.

Back in the day, we standardized practice patterns for head and neck cancer - volumes and dosing. It is historically a very brutal disease with, honestly, a terribly high toxicity treatment path. Today we have a new subset of this cancer - HPV+ disease - where we are trying - quite hard at times, to drastically change where we were guided by history.

This article asks, when is it too far of a leap from those standards? Today, head and neck cancer still recurs even with rather big volumes and high doses and while there are hints that we might be able to de-escalate in some HPV+ disease, we’ve actually run several unsuccessful trials where yes - we reduced the treatment intensity, but unfortunately the cancer recurred more often.

So the question becomes one of balancing. In cases where we are below say 95% control of the disease, should we even de-escalate or just work to improve the cure? If the cure IS currently say 93%, does that give leeway to consider 85% as viable and under what circumstances would that compromise be appropriate? These are tough ethical questions and they lie at the intersection of this trial and proton therapy - at least in some ways. I’ll explain.

In the treatment of head and cancer, we are looking at a few major approaches to attempt to reduce toxicity - mainly focused on HPV+ disease. One major path is to use the tools you have and try to leap forward with less dose, or shrinking the volume of the neck treated or altering chemo. A second path looks to newer surgical approaches like TORS or immunotherapy to aid in altering volumes addressed. And a final approach is to simply swap pencil beam proton therapy for IMRT photon treatment.

And today we’ll consider trial results from a new de-escalation study that results in 5 of 19 patients failing the primary course of head and neck treatment for HPV+ disease within 3 months of the primary treatment course - a disease that probably should have 1 failure for that small number of patients. Here, if no one else fails, we are in the lower 70th percentile range for control - max.

History and Context:

A bit of history. I moved to a proton facility primarily because I had a large head and neck cancer practice. I wanted to look at protons as a way to reduce toxicity for my patients. It is what I would have requested for me or my family both then and now. I understand I’m an outlier in perhaps trusting the retrospective data to the extent I do, but I really do believe the excess dose in the head and neck region between photons and protons, eventually, will be proven to matter. (opinion - today). Regardless, I thought we could do better to reduce the acute and late toxicities by putting more dose into the target and made the jump. And no doubt, head and neck cancer was the primary driver of me relocating.

I was blessed to train at MD Anderson and I think I did 3 or 4 head and neck rotations. We had something like 60-80 head and neck patients under beam with 2 or maybe 3 residents. We saw super high volume. After leaving training and entering practice, the busiest surgeon in the state generally sent stuff to either me or one other guy. I’d say the two of us did the majority of state head and neck cancer radiation for a decade or so. It is more diverse today in that region but hopefully you get the point. Head and neck cancer treatment is one of the areas with my largest volume experience and so relative to most, I have reasonable experience even compared to some focused players a decade into practice - at least that’s my estimate.

And with context, back to our topic.

First off - kudos to the authors on a straightforward - to the point title! If you have a poor result, just put it down on paper and make it easy to note - again well done from that respect.

In the trial, from my perspective, we make a few large leaps from standard of care approaches. Individually, these are all big steps. Together they represent quite a leap. The main changes are:

Using immunotherapy alone as treatment for the subclinical neck

Using immunotherapy to help increase the effective dose of a short course, rather low dose 25Gy / 5 fraction treatment - a dose likely closer to 30/10 than 50/25.

Creating a radiation + Tors approach for the primary in contrast to most instances where we attempt to do one OR the other.

On my first read my initial question was “certainly there is some good support in the literature”. What did I do first? I went to the introduction of the trial which should demonstrate pretty clear rationale for the trial design. Per the introduction, the primary rationale for this approach is mainly 5 trials:

This first trial demonstrated that we can’t drop chemotherapy. We still need treatment beyond just radiation. (As I have said, we’ve really haven’t been successful to date in demonstrating safe de-escalation in a randomized prospective fashion).

The third trial is a one off trial from my review of the literature. It seems promising but then neither the lead or senior authors have published anything else on the topic - like zero. It looks reasonable but small (54 pts) and realistically it adds little to the second reference which we’ll look at below.

The fourth trial discusses that with appropriate selection, local regional failure after TORs is 3.3%. Hmmm.. We didn’t hit that mark. And the final trial referenced in the introduction is a broad discussion of our literature looking at interactions between immunotherapy and radiation but basically concludes - there is a lot to learn - and while the article includes 123 references, ONE directly relates to head and neck cancer or squamous cell cancer. (I’m certain others have to touch upon something, but my point is… it is a general what-if type paper and is not a trial demonstrating good results for any of the steps in the current study).

That leaves one real, to me, reference - again, just going from the data they list as their support for their study per their introduction. This is a really good one:

It’s a great study with excellent results showing that they treated with radiation with pretty significant dose reduction - reducing subclinical dose to 30 Gy in 15 fractions. It is out of Memorial Sloan Kettering with a number of high volume head and neck specialists.

In the study, initial fields are treated to 30 Gy to cover more historical volumes but to lower dose and then there is a 40 Gy in 20 fraction boost to gross disease. The trial demonstrates excellent control at 97% and it limited toxicity - which I think everyone would agree makes perfect sense - a dramatic reduction in dose.

I’d love to see it updated - Data analysis is now 18 months old and it shows an real chance to significantly decrease nodal dose. I asked the authors about the series and they all reported it has become their standard approach at Memorial and they haven’t seen anything concerning. (but I still think it would be worth an abstract or poster at a minimum).

But on my review that really is the data supporting the trial - per the authors from their introduction. Personally, I think it would have been valuable to include much more depth here in what appears to be a failed trial design. Certainly for the IRB, I would hope that they would have addressed the three large steps that I point out above on some level in far more detail - maybe it was a journal constraint - regardless, I would have liked to see more convincing rationale clearly presented.

For reference and for a broader perspective than just mine, let’s go to a well done review article looking at our current approaches in head and neck to achieve a successful de-escalation of our treatment course.

It is a summary of our literature: an article out of University of Chicago - it reviews the broad literature - I think it missing one item which isn’t surprising if you have context. (As I like to say, when you read things, you need to understand the history of the institution, what they like, what they don’t - so you can file these things correctly - context is key).

It discusses four main approaches - I won’t dive into the article too deeply. But it is worth a read to quickly catch up on the topic if interested:

Replacing, Reducing, or Omitting Cytotoxic Chemotherapy

Minimally Invasive Surgical Approaches with De‐Escalated Adjuvant (Chemo)radiotherapy

Reduction in Radiotherapy Dose Following Induction Chemotherapy

Novel Strategies for Selecting Patients for Treatment De‐Escalation

Now lets look at the Phase Ib/II trial: Item one - the trial does this. Item two - again, we integrate surgery with TORS. Item three - we go a step farther - not only completely eliminating dose to the subclinical regions but dropping dramatically the dose to the primary.

Three of the four taken on at the same time - an “all at once” approach.

Just to contrast this trials approach to the Memorial Sloan Kettering approach - the Memorial approach decreases subclinical dose. A single stepwise approach. One I like, one think should be reconsidered and studied more broadly.

Likely I could go and dig and find some additional rationale for each of the three steps that I see in the current trial and better document rationale, but realistically, I’d think the introduction to the trial would be a really good reference - at least I believe it should be. And to me, when you see that 5 of 19 failed within 3 months of the completion of therapy, we need to seriously ask when it is too big of a jump. Not just for this trial - but to step back and reconsider if this question was simply too much to ask in one trial.

Thankfully the paper states all patients have been successfully salvaged. But realistically with a large subset of early failures and numerous salvage cases, I would not personally see the salvage data as valid until about year 5 post-salvage therapy - with a longer look at both control and toxicity. I’m hopeful the authors report, on some level, 5 year results and hopefully the patients have excellent long-term outcomes.

When is it too far?

Obviously I don’t know. Personally, if I were involved I feel quite confident that I do think this result would give me pause. And when I say that, I mean for years along this path. I’d be back at the drawing board trying to figure out how and where I missed and trying to reform my foundation of information. I’d swap to far more conservative approaches and perhaps try to mirror / re-create the Memorial data - not near as “exciting” but certainly more measured.

Ironically, that kind of reassessment has potential to happen here with protons live on this Substack. If you asked me in 2018 where we would be today with proton therapy data, I would have assumed the data would be stronger today. And the window for an obvious big win for protons is closing. Realistically, if the head and neck data and breast RADCOMP data and the repeats of the esophageal and lung data are negative, it will be a time of reconsideration on my part. That is why I started this in 2023. I think we begin to have this data roll out in late 2023 or 2024 and I wanted there to be a clear runway of context. Again goal here is to call balls and strikes.

So what is an approach I like?

I like just jumping back up to the strongest reference they provide - the series out of Memorial Sloan Kettering that appears to demonstrate the ability to significantly reduce dose to regions of the neck at risk for subclinical disease.

In contrast to a series of large leaps, to me, this trial represents a singular stepwise approach. I think that approach in head and neck cancer, where failure can mean so very much is a more appropriate path.

In that trial they reduce subclinical risk regions from ~50 or even ~60 Gy to 30Gy for people with an HPV+ head and neck cancer and demonstrate excellent control. And in that example, where those physician scientists have accomplished something that appears this viable, the publishing team now becomes a group I would prioritize moving forward when I consider which are the more valid /safe approaches.

Slow and steady reduction of volumes and dosing seem like reasonable attempts. Unfortunately today, many de-escalation approaches are proving not successful. I worry that we are trying / pushing too far and, to me, this Phase Ib/II trial is an example of that.

What Did University of Chicago Review Miss?

Protons. Should be pretty easy to guess (consider the context of what you are reading). Makes sense, some institutions love them, some, well… not so much. I think both sides of the proton debate have large issues with bias. I certainly have bias / opinions on how this will play out - despite really trying to look at data - I think on this topic, it is hard not to have some.

But what can protons do from a de-escalation standpoint?

From my perspective, protons are a form of de-escalation. Protons - especially today in the time of pencil beam and robust optimizations dramatically reduce the amount of radiation that you deliver into the patient to achieve a given target dose.

Are there some uncertainties with a jump from IMRT to protons? Yes. But today they are quite limited and I’d argue significantly less than the far more aggressive dose reduction strategies that being experimented with today.

Again, on this site, I try to just bring some the better counter arguments here directly. No point in hiding - I think that adds value. Here is probably the currently most discussed risk - osteoradionecrosis risk following proton therapy that would be an argument against using protons as “de-escalation”. Below are two references - one from Memorial Sloan Kettering and one from MD Anderson - two pretty reasonable institutions. Here one hints at possibly more necrosis and one is less.

Osteoradionecrosis of the Jaw Following Proton Radiation Therapy for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36547968/Intensity-modulated proton therapy and osteoradionecrosis in oropharyngeal cancer

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28549794/

I don’t want to get too side-tracked. I’d just say pencil beam is rather new (10 yrs) and IF there was an increase in distal range osteonecrosis for some cases treated in the first half of that decade, most of this finding has already been addressed via more fields treated per day and better LET optimization understanding, and more availability to cone beam to better monitor SSD changes. Today this is a known risk and can be managed (at least to a moderate extent) via planning and clinical experience.

So yes, until we have real prospective data there are unknowns, but in our non-proton example, 5 of 19 failed in 3 months. And with that context, you can consider the risk / benefit ratio of each approach.

Original Work:

A look at integral dose differences:

Do Protons really represent de-escalation of dose?

I know most facilities do not have access to proton planning so most facilities / physicians can’t look at comparison plans or integral dose differences or where they might consider using protons. I’ve talked to some of the planning systems about rolling this out to help in facilitating our specialty’s adoption of this technology - and they laugh - because they want 100k per install and who would either pay for that as a learning tool and the other option to just give that away??, well that is crazy. But regardless, here is what you see.

The delivered radiation dose reduction moving from traditional fractionation to pencil beam scanning is GREATER than the reduction moving from traditional dose of subclinical disease to 30 Gy to subclinical disease.

To me, that is kind of crazy really - you get to keep known / proven dosing and the delivered patient dose reduction is larger with proton therapy than with drastic reductions in traditional doses.

My Work specifically for this article:

So I pulled up my prior unilateral passive scanning plans where I looked at protons vs. Dysphagia optimized IMRT. Full article linked below:

Protons 101: ORIGINAL PUBLICATION, Dysphagia-Optimized Unilateral Proton Radiation Therapy: A Comparative Study Evaluating Constrictor Muscle Dosimetry

Quick Note: This is a 100% technical medical literature post. Purpose: This study reports dose delivered to the superior middle pharyngeal constrictors muscles (SMPCM) and the inferior posterior constrictor muscles (IPCM) utilizing proton therapy compared to dysphagia-optimized IMRT (Do-IMRT) in unilateral head and neck treatment.

I went back to this dataset and ran two comparative cases for two additional patients. Both came out very similar and integral dose math is integral dose math, so I assume across unilateral treatment this is correct broadly. The “math” (ie planning results) from one of the two example cases is shown below - it is representative of both:

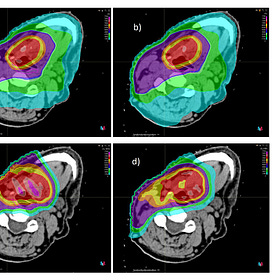

From left to right - we have three planning approaches - subclinical to 30Gy, subclinical to 54Gy>60Gy (integrated boost traditional IMRT approach) and Pencil beam with subclinical to 50Gy>60Gy (non-integrated traditional proton plan). (see paper for rational of non-SIB approach but simply it was a passive scanning paper and SIB in passive approaches is very very difficult to even approximate). DVH shows approximate stepwise results for each approach as expected. I have added a white text box to highlight the average external dose - ie integral dose to the head and neck region.

So in this example, reducing dose to the low neck to 30Gy results in a 30% drop in integral dose delivered to the patient. In comparison, keeping all the same doses, we see a drop 65% with a move to uniform scanning proton therapy - approximately a two fold reduction relative to reducing neck dose to 30 Gy.

A second example that I think illustrates the point differently - this one is back from the time of the original work that I did. It asks, how many times would you need to deliver a 10x10 field of 6MV photons into the head and neck region at 2 Gy specified to Dmax to equal out the radiation delivered into the patient between IMRT and a proton therapy plan.

In the example above, the answer was 39 times. 7800 cGy delivered at 2 Gy into the head and neck region somewhere above the clavicle to have the same integral dose to the patient.

Note: pencil beam will always be a bit superior to uniform scanning even when it is a “good” uniform scanning unilateral case because pencil beam lets us decrease the entry dose - with uniform scanning this region is essentially full dose when all beams enter and intersect in the superficial regions. This is not the case in pencil beam where, similar to IMRT, you can choose to cool off the superficial tissues.

Honestly, don’t get hung up on the exact numbers. As we iterate with protons, the integral dose will move around a bit between 2 field or 4 field or 5 field approaches and how the multi-fields are optimized but I think the premise on the trend remains in place:

Protons treated to traditional doses represent a far larger reduction in dose to the patient as reducing subclinical dose to 30Gy in the treatment of HPV+ disease when each are compared to IMRT in unilateral treatment approaches.

Hopefully this demonstrates the “potential” for protons in this space. Clinically, it is quite apparent when caring for these patients - I believe that. When the authors from Memorial reported that they see much less toxicity, it was not questioned. It is an “of course” reaction. My hope is in the next few years, with the backing of much needed data, we get to that point in many head and neck cases for the use of proton therapy.

De-Escalation shrinks the black box:

In my last article, we discussed shrinking the black box - making it more and more difficult to prove benefit for things like AI histology or genetic testing to prove benefit that attempt help parse out why some low numbers of patients, even into favorable intermediate and low grade appear to benefit from short term ADT from a cancer control perspective.

Successful de-escalation - or as I stated - finding the correct dose and correct target volume precisely shrinks the opportunity for these new technologies. It is a similar approach here but within a very different context.

Here, in head and neck cancer - specifically in HPV+ where we believe more strongly today in our ability to find a successful de-escalation path - approaches like the one at Memorial will exert the exact same pressure on protons. There simply is less room for benefit. It is the hazard rate discussion we just had, repeated and almost flipped upside down. This time, instead of arguing against genetics or something outside our field, it will argue against the odds of proton therapy demonstrating benefit. And, yes, I see that as great! As I’ve said here before, nothing we do today is good enough.

In my example above, the resultant gain using protons dropped from an average dose of 600cGy to basically half of that difference to 300cGy. Much less of a difference - not zero, but more difficult to discern? Absolutely.

And looking forward, protons must demonstrate that they reduce toxicity in the treatment of head and neck cancer - if EITHER the OPC trial or the DAHANCA trial fail to demonstrate toxicity improvements, we (the proton industry) needs to seriously re-think a path forward as the "potential space” for protons to demonstrate improvements would then be clearly VERY small. This would mean it didn’t work in a highly toxic, clear strong retrospective data cohort, with clear and impressive integral dose data, and modern trial design with pencil beam and modern planning - simply there are no good excuses left and the window for a real opportunity to be better would then be very limited.

But I would note: the limitations of passive scanning approaches are real. Surface dose, time / complexity and limited applicable uses - especially relative to pencil beam. If you are currently hanging your hat on the older approaches not showing improvement over decades (which is a completely valid criticism), I’d suggest you tread carefully. Planning improvements, beam arrangement improvements, better understanding of the platform in general and better integration of CT treatment imaging are all real improvements for the proton side of the of the ledger.

The main arguments I see against the above data I presented are those that argue that - similar to prostate cancer - the toxicity is driven by the high dose volume and therefore the planning data I presented are irrelevant. I do think that is, at least in part, valid. For prostate it absolutely holds the majority of our toxicity. In head and neck cancer, I’m far less convinced that 30Gy covering the oral cavity is anywhere near the same as 30Gy through the hips and buttocks. Hair loss, salivary function, the brutal-ness of the treatment - I think they are different - and I believe that will be demonstrated in our prospective data.

So, on record, I think both the OPC trial and the DAHANCA trial and the subsequent meta-analysis combining the two will be positive demonstrating toxicity reductions. It is my understanding that we are within one year of this data beginning to come out. At which point, if I’m correct, the data supporting proton therapy in head and neck cancer would be far stronger than anything supporting IMRT over 3D. And there will be reckoning in our field if that is the case. Which gets me back to the unsuccessful trial that changed so much and was quickly noted to be - an incorrect path.

The Reception of Protons as a De-escalation path:

If the data favors proton therapy, the national reception of this prospective data, I believe, will be a reactionary VERY STRONG push towards skipping steps in the de-escalation of head and neck cancer that will place patients at significant risk of failure as, at least in the US. The need / desire to treat patients “in house” is very ingrained - and a rapid expansion of this “opportunity to de-escalate” approach will happen. It will happen too broadly and too quickly. If you think it is popular now, wait until the other option is to refer outside the institution for proton therapy. That is my concern and I believe it is quite real.

Already today, as we have reviewed, we are pushing quite hard to de-escalate. The Phase Ib/II trial is not something that I believe I would have consented to, for either me or my family unless I was presented with far more background data than I found in my week or so dive deeper into some of our data. To me, it was a bridge too far.

If I had an HPV+ head and neck cancer, would I de-escalate my subclinical dose to 30 Gy? and further, would I pair that with proton therapy to deliver far less than half of the dose into my head and neck region? Yep - those seem very reasonable and supported based on the data I have seen. In fact, I see little reason NOT to do those simple approaches - and I guess that is where I differ from many - I see protons in head and neck cancer (due to massive toxicity) as part of the solution and reasonable.

And if I had an HPV- cancer and radiation was the primary pathway (with or without chemotherapy), today prior to prospective data, I would travel for protons as my primary pathway to de-escalate treatment toxicity. And if the prospective data is, as I think it will be, positive for toxicity reduction, the goalposts must shift for these de-escalation approaches to include protons as an alternative path.

Protons are not the only path forward. But from a radiation standpoint, they represent one of our primary options to reduce normal tissue dose and whenever we are opting to consider de-escalation trials, I think it is reasonable to consider a comparable path to de-escalation via protons. Consider again the massive dose differences I presented above. As I’ve said, it is going to be an interesting couple of years as we grapple with terribly complex issues in our specialty.

In the end - I love making progress towards better outcomes. I do not question the motives of anyone looking for better. But I do have concerns about large steps that break away from our history - a history built on head and neck cancer as one of our primary indications.

The doses and volumes that we used can certainly be tweaked and improved but they didn’t come from nowhere.

Evaluation of the dose for postoperative radiation therapy of head and neck cancer: First report of a prospective randomized trial

Lester J Peters, M.D., Helmuth Goepfert, M.D.,K.Kian Ang, M.D., Ph.D., Robert M Byers, M.D., Moshe H Maor, M.D., Oscar Guillamondegui, M.D., William H Morrison, M.D., Randal S Weber, M.D., Adam S Garden, M.D., Robert A Frankenthaler, M.D., Mary J Oswald, B.S., Barry W Brown, PH.D.

A list of pretty bright people - some of whom literally make the list of the smartest people I have personally known and had the privilege to work alongside. To stand still is clearly incorrect as progress is mandatory, but to not strongly consider and question each small decrement in treatment is, to me, unwise. Recurrent disease in head and neck cancer is a real risk and using tools and approaches which allow de-escalation while minimizing the chance of increased failures seems pretty reasonable.

Hopefully that is why you are here - for content - and to see things presented from a different perspective - I can’t do much better than to show you original analysis from planning software. (hint: I don’t have a personal randomized trial coming forth). Clearly I have a strong slant in favor of proton therapy for head and neck cancer. I think it holds real potential for a minority of cases where we struggle to limit dose beyond our target and cause real toxicity risk. That said, protons are clearly controversial - mainly the whole cost / money thing, and maybe some day soon, I’ll address some of that more directly.

But today, thanks for reading and supporting the work. Help spread the word and have a great week.

REFERENCES:

High Recurrence For HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer With Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy To Gross Disease Plus Immunotherapy: Analysis From a Prospective Phase Ib/II Clinical Trial

https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(23)00432-7/fulltextYom SS, Torres-Saavedra P, Caudell JJ, et al. Reduced-Dose Radiation Therapy for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (NRG Oncology HN002). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(9):956-965.

Tsai CJ, McBride SM, Riaz N, et al. Evaluation of Substantial Reduction in Elective Radiotherapy Dose and Field in Patients With Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma Treated With Definitive Chemoradiotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(3):364-372.

Maguire PD, Neal CR, Hardy SM, Schreiber AM. Single-Arm Phase 2 Trial of Elective Nodal Dose Reduction for Patients With Locoregionally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(5):1210-1216.

Kaczmar JM, Tan KS, Heitjan DF, et al. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer: Risk factors for treatment failure in patients managed with primary transoral robotic surgery. Head Neck. 2016;38(1):59-65.

Combining Radiotherapy and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Paradigm Shift

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3576324/