AI Enters the Landscape of Prostate Cancer

Part 1: Today we'll look at highlights of a new study in prostate cancer.

RTOG 9408 treated men from 1994 - 2001 (exactly my radiation oncology training years) And I am now old, or at least mildly mature. 1994,95 short rotations in RadOnc, 96 transition year, 97-01 MDACC). It gave 66.6 at 1.8 Gy per fraction: 63.27 EQD2(2).

And the AI result? (or at least my version of it):

If you treat to 64 Gy for unfavorable risk prostate cancer - giving everyone ADT is STILL NOT needed. (even though recommended for all patients per NCCN). In fact, 2 out of 3 men with unfavorable disease you are over-treating with ADT.

Let that sink in.

In a very direct way, it would seem to validate quite a few of my “non-conformist” views regarding ADT utilization that I’ve presented here on this Substack - at least from my perspective.

Of course, the other side of that coin is how best to pick the 33% that do benefit - if in fact that “answer” is “correct”. What is the best approach to find the that cohort that truly benefits? And are you going to start giving ADT for low risk disease based on a computer derived answer? So many questions!

A recent body of work attempts to use an AI approach to use existing factors along with an AI review of the pathology slides to make a new “predictive biomarker” to guide your path. And in the next two articles, we’ll discuss that approach.

First things first, if I spend a week or two or so digging through an article and cross-referencing items and diving into the supplemental appendixes, I believe it carries value. Here I think the question is how much value? Maybe how should it be developed? What role will it serve?

It ends up working best as two articles, but that is ok because the topic is critical to so many concepts here on the site, I didn’t want to rush, and it will tie into a longer term of goal of reviewing the Decipher data. As you read, this is the interpretation of one - how I might want to see a upper resident consider a new paper.

And with that, we’ll begin and see if you agree or disagree with the assessment.

Today’s topic:

Artificial Intelligence Predictive Model for Hormone Therapy Use in Prostate Cancer

The resident exercise would be to read the paper, make their own assessment - dig as deep as you deem necessary, and then return here to complete the puzzle and self-assess the two perspectives.

The Premise:

Here is the original thread laying out the premise. I encourage you to read it - it carries a lot of context. I’ll repeat highlights here, but as always, please consider both perspectives and go from the original sources:

X-torial

The argument for this new tool begins with the argument that ADT offers benefit in intermediate risk disease.

It is supported by quite a bit of hazard rate data in the history of literature across a range of doses that appear to demonstrate a similar hazard rate reduction in some important clinical outcomes (like DM rate or even prostate cancer specific mortality). And then argues that despite all the current methods we use to parse prostate cancer, we still don’t have a great way to predict who and when exactly they might need ADT.

And to be clear, I agree with that. As I lay out below, I believe I just see different weightings of importance - as I’ve argued, I do not see one perspective as right and the other as wrong, but rather two views of the same coin. Here is a link to that discussion and I pulled one quote that seems quite pertinent:

RTOG 0815: Dose Escalation and ADT. Questions answered?

Let me begin by saying this is a study to know - an important part of our literature - it is that well done. Kudos to all involved! Today we’ll look at some components from perhaps a different perspective. This discussion is likely a bit different than the more common narrative and as usual, I might very well be wrong and the narrative supported by many…

The counter to this argument is to use radiation specific technology to push on dose and right sizing the target - essentially to shrink the size of the black box of unknowns. Stated differently, I’d like to make the work in finding the genetic difference as difficult as possible by using brute force to push the number at risk for failure as low as possible. If 30 people in 100 fail, the cost / benefit ratio for any prognostic test is magnitudes easier to achieve than if 5 in 100 fail. Will it make the other approach obsolete? No. But we can make it far less impactful. I think of it as an argument in favor of our field and in favor of the value we provide.

One approach leans on radiation a bit more, one leans towards tech that is generally beyond our field a bit more.

Quite simply I’ve laid out the rationale for why I treat only about 1 in 4 men with unfavorable risk disease with ADT and almost never treat anyone with favorable intermediate risk disease via several articles on this site. I’ve laid out the kinetics that point to 5 yr outcomes in excess of 90% and why I believe we should be seeking results that obtain a mean PSA at 1 yr < 1 and a mean PSA post treatment at 2 yrs of 0.5 or less.

If you meet those standards, however you do it, in non-ADT treated men, you will have excellent long-term disease control. Might some “do better” with ADT even still? Likely, but a diminishing minority.

So I think we differ on perspective a bit while, at the same time, appear to agree on many components of the basic premise.

The Validation Study:

Validation will revolve around 9408 - let’s just review the biochemical disease free survival curves for the trial.

Remember - for this trial we got 5 year biochemical disease free survival somewhere in the LOW 70s. At 10 years, nearly half failed when treated with radiation alone. Certainly with PSMA scanning we’d find more failures and that number would be at least 10%-20% higher.

So yes while ADT continues to have a hazard rate improvement that appears quite stable regardless of dose level, the absolute benefits can vary significantly - and to me, when discussing risks with a patients, the more pertinent is absolute benefit.

Below is a post-hoc analysis of 9408 that is used to make the argument that the curves - even in FIR favor ADT if anything. The argument being there is some small subset, even into actual low risk disease where ADT - if you knew everything in the “box of unknowns” - would demonstrate benefit.

Maybe. Little in medicine is that ideal. Life and organisms are vastly complex and somethings are best viewed as stochastic / random events. But here in these particular curves, there is something else going on. It is almost as patients literally died of prostate cancer within weeks of not receiving a Lupron injection in both the FIR and UIR curves. Obviously there is some confounder. Today. there is no way curves should separate within 2 years - no way - these separate early (before 3? months). Simply no way - or at least 0 known events in my ~300 patient tracked cohort including high and very high risk patients.

And so while it still might be true that there is some difference - this clearly has some other confounding factor favoring the ADT arm. Is it worth my time to dig further? I don’t believe it is. And so mentally, I file this data as “less sound” - curves clearly have confounders. Maybe on some level true but at a minimum, this appears to overstate differences. But make a mental note, this clear bias lies in PCSM - where the model will work.

But the premise stays on point:

Some FIR patients benefit and more UIR patients benefit.

That I completely agree with. I guess my only question is size of the cohort and IF the FIR group that benefits is in fact 1%, that is quite different from 5% when it comes to a decision on ordering a “predictive” test.

The Model:

The central feature of the article is to create a model that attempts to predict ADT necessity. The primary component is a computer read of the slides ie how aggressive does the computer “see” the pathology. My understanding is it is a form of AI: multi-modal deep learning - not generative like ChatGPT where the application continues to have a moving “black box of information” (my words) but we’ll come back to that in Part 2.

Below are the model components:

The four primary factors in the model are the slides, comprising over 87% of the information - only T-stage, age, and PSA are not included. Everything else is slide related. Again, from my perspective, this is both a potential strength and weakness which we will come back to in Part 2 of our discussion.

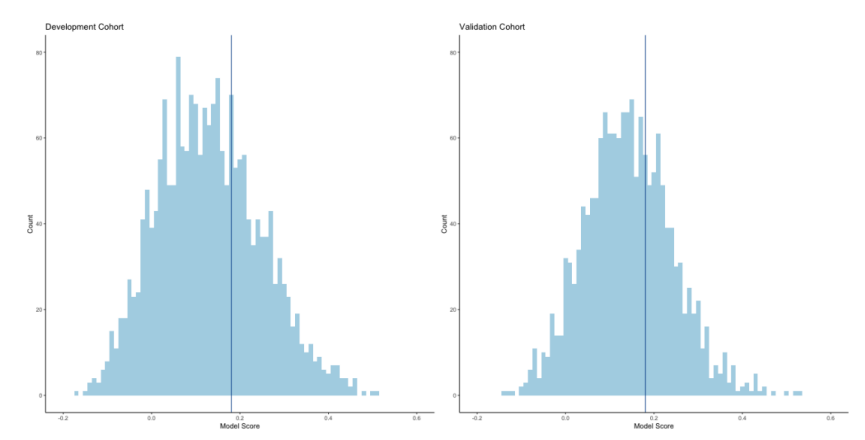

As you would expect, the model creates a range of values. The authors then assign a single “best” cutpoint to data. While this is pretty common in today’s literature, the math behind it is less robust than the conclusions that one often will draw - ie it can make great graphs on a particular dataset but presentations point to a dichotomous result when in fact, it is a continuous variable. I’ll come back to this issue as well in Part 2.

Keeping it simple, they created the model using other randomized studies and then locked the model down and then ran a validation test on the 9408 trial. Impressively they were able to use 1600 of 2000 men - one slide for image analysis and the other 2/3rds of the model are previously known clinical factors which include Gleason score. The authors note that this is a significant advantage over other approaches like Decipher where you simply can’t go back this far and run validation studies. I agree that this is really pretty slick.

And finally, The Results:

It worked! The model parsed the cohort. In the study 2/3rds of men - based on this AI approach do NOT need ADT according to the AI. 1 in 3 do.

While 2 in 3 men see basically no benefit, the 1 in 3 men see an increase in absolute benefit of 3.9% increasing to 10.4% - nearly 3x consistent with ratio of model positivity to model negativity.

And here was the kicker so to speak: It doesn’t appear to line up with Gleason or risk grouping - the 2 in 3 not needing ADT is consistent across Gleason score and Risk Grouping.

But not all Roses:

Metastatic Free Survival and OS fall apart

If you dig, there is more data in the Supplemental data. I think the one below is interesting as it adds more questions than answers. It looks at just the low risk and intermediate risk patients and shows that for metastasis free survival and for overall survival, the model didn’t really work at all. In fact, if anything it trends towards worse outcomes if model positive (ie model believed it should give ADT).

So while the headline is the distant metastatic prediction and prostate cancer specific mortality prediction is good: the Supplemental data shows metastasis free survival and overall survival actually fall apart - if anything trending the wrong way. There is a second similar graph showing this is also the case for the entire cohort (ie one that includes high risk).

The discussion of the paper does specifically take on this issue addressing some rationale for the difference between PCSM and MFS. Here are two quotes:

MFS and overall survival are important end points for determining the net effect of a given therapy and are the gold standard for clinical trial design because they also capture death from competing causes. However, they are suboptimal end points for development of prostate cancer–specific predictive models for localized disease.

Importantly, despite the model being trained for distant metastasis, it showed a clear differential impact of ADT by predictive model status for prostate cancer–specific mortality, a cancer-driven end point.

But make a mental note and we’ll circle back in Part 2 as to why this doesn’t quite answer my concerns.

And that is what we get. Just when it is starting to get good, that is the article. Presenting a lot of work yet leaving so many questions - at least from my perspective.

Quick Aside:

To me this is a problem in modern medical publications. We get a pieces of a puzzle. I’m not saying this doesn’t represent a ton of work - it literally appears to be a ton of work. But it is represents only part of what I believe we need to see.

Back in the day, a paper might represent several years of dedicated work - for one publication. You simply can’t function like that today. Perhaps the work is too complex and too many hands are required, but in a real way, the pressure to publish an exponential number of publications has degraded the literature. Just last week ago I reviewed authors publishing two different PSA kinetic analysis less than two weeks apart recommending different “answers”.

I *think* this has potential to be brilliant work (a word not chosen lightly), but I need to see much more comparative data and more breakdowns of the data, ideally in a modern dataset, which we’ll discuss next week. As of right now, if offered the ability to order it, to me, supporting data isn’t strong enough - too complex without enough simple comparisons. Interesting work that adds to the literature? Yes. Data to watch? Most certainly. Ready for prime time in the clinic? From my perspective, no - at least with the presented data to date. And I don’t think that is much different than the Discussion or Conclusions state - so well done to authors there.

In Closing:

We’ll leave today with a few thoughts to ponder for Part 2:

Here is RTOG 9408 patient mix - read and remember the outcome curves:

Low Risk: 360 (36.6%) 343 (34.6%)

Intermediate Risk: 530 (53.9%) 556 (56.2%)

High Risk: 94 (9.6%)91 (9.2%)

Today, I treat essentially no favorable risk disease and only about one in four men with unfavorable risk disease with ADT. The number needed to treat from this analysis is presented as 10 in the X.thread (haha).

Next week we’ll look at how this type of practice information can dramatically impact the number needed to treat and see if there are additional analysis that would assist clinicians in deciding when and where and how to integrate this potential tool into their clinical practice.

And further, we’ll look backwards at an earlier presentation of a very similar AI model approach - and a look into the datasets that make up that first paper and then this “validation” trial. This one takes a bit to unpack, but I think worthwhile in the end.

Part 2: Now Released:

AI enters the Prostate Landscape: Part 2

Last week, we looked a new paper: Artificial Intelligence Predictive Model for Hormone Therapy Use in Prostate Cancer

Thanks as always for reading along as we search for better. If you learned something, or even if you might consider things with a slightly different perspective, please consider subscribing or sharing this Substack.

Great job with the in-depth commentary. I think this passage in the Discussion adequately addresses your concerns about OS and MFS prediction: “This is because 78% of deaths in the validation cohort were not from prostate cancer, and only 12% of events in the MFS end point were from metastatic events. Thus, the strongest prediction models for MFS and overall survival would be driven by variables associated with death from nonprostate cancer causes (i.e., comorbid conditions). Importantly, despite the model being trained for distant metastasis, it showed a clear differential impact of ADT by predictive model status for prostate cancer–specific mortality, a cancer-driven end point.”

If you’re training a prediction model, I would think it’ll always fall apart when you ask it to predict death from non-cancer causes (which is the case for OS and MFS).

I reviewed the titles of all the supporting publications Decipher’s owners list on its website, and I don’t see any that rigorously evaluated predictive performance for benefit from ADT in the IR population the way Artera did. Take a look and let me know if I’m wrong: https://decipherbio.com/resource-publications/#publications .